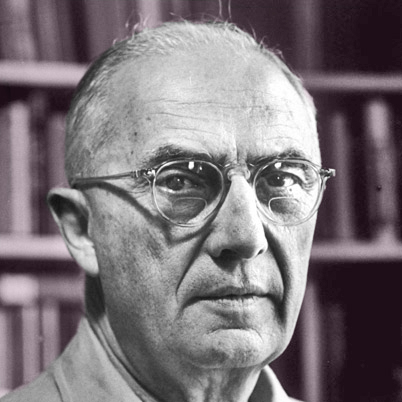

This letter, from poet William Carlos Williams to Ezra Pound, illuminates their strange and fraught friendship. Both rivals and intimate confidants, Pound and Williams found conflicting personalities in one another. Williams, here, ponders verse.

June, 1932

Dear Ezra: I’ve been playing with a theory that the inexplicitness of modern verse as compared with, let us say, the Iliad, and our increasingly difficult music in the verse as compared with the more or less downrightness of their line forms—have been the result of a clearly understandable revolution in poetic attitude. Whereas formerly the music which accompanied the words amplified, certified and released them, today the words we write, failing a patent music, have become the music itself, and the understanding of the individual (presumed) is now that which used to be the words.

This blasts out of existence forever all the puerile ties of the dum te dum versifiers and puts it up to the reader to be a man—if possible. There are not many things to believe, but the trouble is no one believes them. Modern verse forces belief. It is music to that, in every sense, when if ever and in whoever it does or may exist. Without the word (the man himself) the music (verse as we know it today) is only a melody of sounds. But it is magnificent when it plays about some kind of certitude.

Floss has just brought me up an applejack mint julep which I enjoy.—We do produce good applejack in Jersey—and Floss can mix ’em.

Confusion of thought is the worst devilment I have to suffer—as it must be the hell itself of all intelligence. Unbelief is impossible—merely because it is impossible, negation, futility, nothingness.—But the crap that is offered for sale by the big believing corporations—(What the hell! I don’t even think of them, it isn’t that). It’s the lack of focus that drives me to the edge of insanity.

I’ve tried all sorts of personal adjustments—other than a complete let go—

Returning to the writing of verse, which is the only thing that concerns us after all: certainly there is nothing for it but to go on with a complex quantitative music and to further accuracy or image (notes in a scale) and—the rest (undefined save in individual poems)—a music which can only have authority—as we—

I’m a little drunk—

Contact can’t pay for verse or anything else. I mentioned to Pep West that you had more or less objectionably asked me if I was doing this (editing, publishing) Contact in order to offer you a mouthpiece—I told him I had told you to go to hell. He said he’d be mighty glad to have a Canto, that he thought them great.

But we can’t pay a nickel—

The Junior Prom at the High School: Bill is taking his first girl (after an interval of five years). The fishing period and girl-hating has passed again. This one has taught him to dance—he is getting ready to take a bath—now when it is almost time to leave the house.

Yes, I have wanted to kick myself (as you suggest) for not realizing more about Ford Maddox’s verse. If he were only not so in approachable, so fine nowadays. I want to but it is not to be done. Also he is too much like my father was—too English for me ever to be able to talk with him animal to animal.

It’s the middle of a June evening.

No news—much I’d like to do.

Yours,

Bill

FURTHER READING

For a Yale University lecture on Imagism in Williams’ poetry, click here.