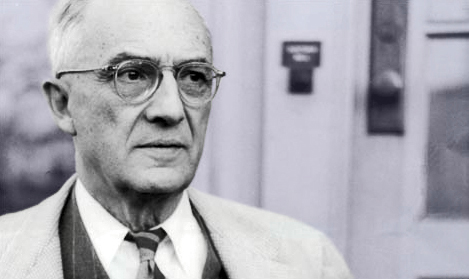

Below, William Carlos Williams writes to Ralph Nash, editor of Perspective magazine. In the autumn of 1953 Nash published a vivid response to Williams’s prosaic use of language in the forth installment of his epic, Paterson. Critics had thus far evaded consideration of the poem’s heavy use of parataxis and newspaper-like observation of quotidian details. Nash attempted to connect the language of Paterson with the industrial city it describes, noting that its mosaic or participational form allows “a forceful marriage of [the] poem’s world with the world of reality.” Williams, as his letter demonstrates, was deeply moved.

To Ralph Nash

January 20, 1954

My dear Ralph Nash: When I read, or had read to me, your article on my use of prose in my poem Paterson, I was left speechless. It has taken me until now to re-establish my equilibrium so that I feel only now in a trustworthy mood to write to you. You have penetrated to a secret source of whatever power I possess and it has frightened me. Fright was my first impression and that also stopped me cold because one does not like to be laid bare that anyone that runs may read! I felt that my very hairs were moving on my head, actually I could feel my scalp move.

For no one to the present moment has so looked within me, if anyone has been interested in me enough to make the attempt, to discover why I have used prose as I have used it. But the point for me is that I have not myself gone sufficiently beyond instinct, very often, to discover the reasons. It is too deep-seated for that and goes to the very core of why I am a writer. You have laid me bare, as I say, for whatever I am worth, something, a feeling which very often the world of my contemporaries tends to break down. It has been a revelation which, as I say, is frightening.

I shall have to study the distinction you make between your observation of what I have done, for it strikes me as on the whole so just and acute an observation of my style that I still can’t believe it. You have gone right down into the reasons which lie behind it. A man must, without relinquishing any of the reasons for the poetry with which he surrounds himself and with which the greats of this world, at their most powerful, surround him, fight his way to a world which breaks through to the actual. This has always been my most pressing concern, not always clearly envisioned but there nevertheless. It has always stood between me and Ezra Pound, for instance. In my reference to Hipponax, the Greek in Patterson, you can again see it breaking out. You have spotted it in my insistence on the use of prose within the poem itself, when I did not see the reasons so clearly and that’s why I think it is so remarkable.

What the secret reasons are for this I do not see very clearly, but that it has a reason and an important one you have made or begun to make clear by your inspired and clinching analysis. This I know, and that it goes deep. It has much to do with the whole of poetry, and what must be its place in our world, which is not its classic place, I have striven to emphasize as best I could; but something closer to us and more important to us besides, I have been much impressed by what you have put down.

Sincerely yours,

W.C. Williams

From The Selected Letters of Williams Carlos Williams. New York: New Directions Publishing (1957). pp. 323-324.

FURTHER READING

The Paris Review interviews Williams at the close of his life.

Map of the proto-industrial city with a detailed topography of the poem’s language.

“Something urgent to say”: the recent Williams biography.