Here, Lorca writes to Guillén, another member of the acclaimed Spanish Generation of ’27, about a literary supplement starting up in Granada. He goes on to express excitement about his brother’s foray into writing, and his ambivalence about the state of his own poetry. The rooster drawing and playful digression, inspired by the “gallo” in the name of the supplement, is characteristic of Lorca’s lighthearted letter-writing style.

FIRST LETTER

Dear Jorge:

I’m sending you these poor things. You choose and publish whichever you wish. Once you have published them, RETURN THEM TO ME. Will you do it, Guerrero? Yes. Good.

They are bad things. At times I despair. I see that I’m not fit for anything. They are things from 1921. From 1921, when I was a child. Perhaps someday I will be able to express the extraordinary real drawings that I dream. Now I have a long way to go.

I’m far away.

Jorge, write me. Tell Teresita [Guillén’s daughter] that I’m going to tell her the story of the little hen with the trailing dress and yellow hat. The rooster has a very big hat for rainy weather. Tell her that I’ll tell her the story of the frog that played the piano and sang when given little cakes. And lots more.

Adiós. A hug from

Federico

(least of the poets in the world,

but your friend)

SECOND LETTER

Dear Jorge:

The fellows in Granada are going to do a literary supplement for the local paper, Defensor de Granada, with the title El gallo del Defensor. It’s illustrated by Dalí. Falla’s publishing a magnificent article on it. Send something. Whatever you wish. For the first issue. Look how many things I’ve sent you.

Right now I’m terrified and weighted down by something superior to my strength. It seems that Xirgu is going to premiere Mariana Pineda (a romantic drama). Writing a romantic drama was fine three tears ago. Now I see it as peripheral to my work. I don’t know.

[Drawing of a rooster]

Send me

poetry or

prose.

Cock a doodle doo.

We’re very busy now with this rooster, and we’re hoping for success.

I’m crazy with happiness. Don’t say anything to anybody. But my brother Paquito is writing a marvelous novel. Just that: marvelous. And it’s nothing like any of my things. It’s delightful. Don’t say anything yet. It will be a tremendous surprise. I’m not blinded by the infinite love I have for him. No. It’s a reality. I’m telling you this because you’re so much a part of me. It’s a release for my happiness. My brother was inhibited by my personality (you understand). He couldn’t blossom next to me, because my impulse and my art scared him a bit. He had to get away, travel, meet the world on its own terms. But there it is. The poor guy is studying for a professional position in I don’t know what field of law and he’ll succeed so as not to displease my parents. He’s a great student and he’s a protégé of the entire faculty of the University. But what a great man of letters! He is destined to surpass those now writing. Last night I was comparing his prose and his style with that of Salinas and Jarnés, just to give you highly regarded modern examples, and he has a distinct charm, clearer and more youthful than theirs. Besides, it’s a long novel he’s writing. A novel imbued with the Mediterranean Sea. Listen, he’s written a chapter on a beauty contest at the baths of Málaga which is stupendous. This is one of the surprises. He’s going to start to write for El gallo. And so will Enrique Gömez Arboleya, sixteen years old, who’s written a story, Lola y Lola, delightful. The ineffable child whom we call Don Luis Pitín will also be writing stories of witches and sprites, the most imaginative you can imagine, and others who are just as good.

Among all of them, your poetry! Let’s have that joy of rhythm and verse to enrich and crown the magazine!

I hope that Verso y Prosa and El gallo will be the closest of friends and love each other. You will beat our drum, and we’ll proclaim in capital letters: Real Verso y Prosa! The only thing that frightens me is that everything I say seems marvelous to them and that’s not good.

Adiós, Jorge. Regard to [Juan] Guerrero [Ruiz] and confer on him (in my name and that of the magazine) the shield of Alhamar!

A big hug. Answer me, man. Answer me it’s not right that you should write to Vela who is a putrid Ortegista, and not to me. That displeases me. I’m not intelligent. That’s true! But I am a poet.

Federico

Germaine, when are you coming to Granada? Why not this Carnival? Everybody gets together on the main street to see the masquerades, and the best of Granada is on its own and on fire. It would be delightful, because you’d be able to catch, on the sly, the ultimate enchantment of the city.

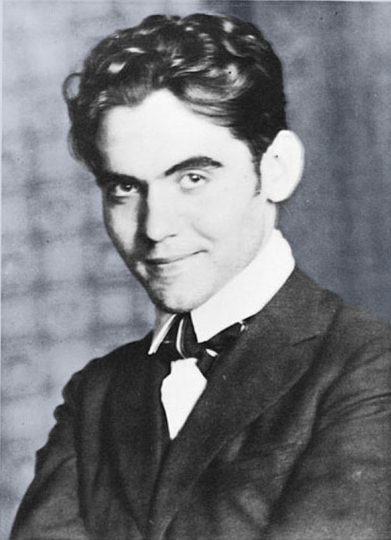

From Federico García Lorca: Selected Letters. Lorca, Federico García, and David Gershator. New York: New Directions, 1983.