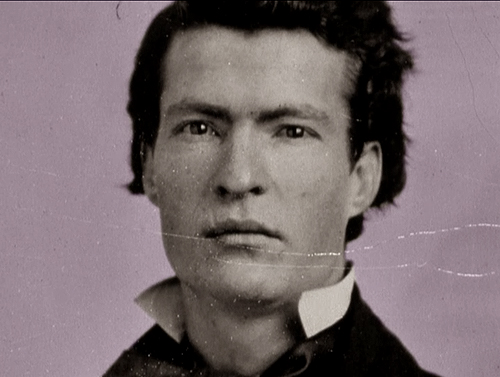

In this emotional letter from his days as a Mississippi River steamboat pilot, 23-year-old Samuel Clemens (pen name: Mark Twain) gives his sister-in-law news of the accident that killed his brother Henry, 19.

Memphis, Tenn., Friday, June 18th, 1858

Dear Sister Mollie,

Long before this reaches you, my poor Henry, my darling, my pride, my glory, my all, will have finished his blameless career, and the light of my life will have gone out in utter darkness. O, God! this is hard to bear. Hardened, hopeless—aye, lost—lost—lost and ruined sinner as I am—I, even I, have humbled myself to the ground and prayed as never man prayed before that the great God might let this cup pass from me, that he would strike me to the earth but spare my brother, that he would pour out the fullness of his just wrath on my wicked head but have mercy, mercy, mercy upon that unoffending boy. The horrors of three days have swept over me. They have blasted my youth and left me an old man before my time. Mollie, there are gray hairs on my head tonight. For forty-eight hours I labored at the bedside of my poor burned and bruised but uncomplaining brother, and then the star of my hope went out and left me in the gloom of despair. Men take me by the hand and congratulate me and call me “lucky” because I was not on the Pennsylvania when she blew up! May God forgive them, for they know not what they say.

Mollie, you do not understand why I was not on that boat. I will tell you. I left Saint Louis on her but on the way down, Mr. Brown, the pilot that was killed by the explosion (poor fellow), quarreled with Henry without cause, while I was steering. Henry started out of the pilot house. Brown jumped up and collared him—turned him half away around and struck him in the face! —and him nearly six feet high—struck my little brother. I was wild from that moment. I left the boat to steer herself and avenged the insult. And the Captain said I was right, that he would discharge Brown in N. Orleans if he could get another pilot, and would do it in St. Louis, anyhow. Of course both of us could not return to St. Louis on the same boat. No pilot could be found, and the Captain sent me to the A. T. Lacey with orders to her Captain to bring me to Saint Louis. Had another pilot been found, poor Brown would have been the “lucky” man.

I was on the Pennsylvania five minutes before she left N. Orleans, and I must tell you the truth, Mollie—three hundred human beings perished by that fearful disaster. Henry was asleep—was blown up—then fell back on the hot boilers, and I suppose that rubbish fell on him, for he is injured internally. He got into the water and swam to shore, and got into the flatboat with the other survivors. He had nothing on but his wet shirt and he lay there burning up with a southern sun and freezing in the wind till the Kate Frisbee came along. His wounds were not dressed till he got to Memphis 15 hours after the explosion. He was senseless and motionless for 12 hours after that.

But may God bless Memphis, the noblest city on the face of the earth. She has done her duty by these poor afflicted creatures, especially Henry, for he has had five—aye, ten, fifteen, twenty times the care and attention that anyone else has had. Dr. Peyton, the best physician in Memphis (he is exactly like the portraits of Webster), sat by him for 36 hours. There are 32 scalded men in that room, and you would know Dr. Peyton better than I can describe him if you could follow him around and here each man murmur as he passed, “May the God of Heaven bless you, Doctor!” The ladies have done well too. Our second Mate, a handsome, noble-hearted young fellow, will die. Yesterday a beautiful girl of 15 stooped timidly down by his side and handed him a pretty bouquet. The poor suffering boy’s eyes kindled, his lips quivered out a gentle, “God bless you, Miss,” and he burst into tears. He made them write her name on a card for him, that he might not forget it.

Pray for me, Mollie, and pray for my poor sinless brother.

Your unfortunate brother,

Saml. L. Clemens

P. S. I got here two days after Henry.

FURTHER READING

Mark Twain later described the disaster on the Pennsylvania in his 1883 memoir Life on the Mississippi. Read his full account here.

For an interactive exhibit of Twain’s various signatures, click here.

More of Twain’s letters and other papers, with annotations and commentary, can be found here in the archives of the Mark Twain Project Online.