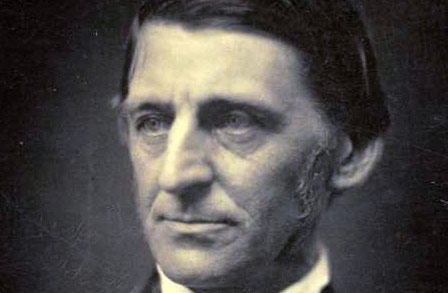

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

In 1831, J.S. Mill introduced Thomas Carlyle to a young New Englander—then traveling abroad in London—by the name of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Jane Carlyle would refer to this first encounter with Emerson as “the visit of an angel”, while Thomas Carlyle would be moved to begin what would eventually become a decades-long correspondence with Emerson.

TO THOMAS CARLYLE

September 17, 1836, Concord MA

My Dear Friend,

I hope you do not measure my love by the tardiness of my messages. I have few pleasures like that of receiving your kind and eloquent letters. I should be most impatient of the long interval between one and another, but that they savor always of Eternity, and promise me a friendship and friendly inspiration not reckoned or ended by days or years.

Your last letter, dated in April, found me a mourner, as did your first. I have lost out of this world my brother Charles, of whom I have spoken to you—the friend and companion of many years, the inmate of my house, a man of a beautiful genius, born to speak well, and whose conversation for these last years has treated every grave question of humanity, and has been my daily bread. I have put so much dependence on his gifts that we made but one man together; for I needed never to do what he could do by noble nature much better than I. He was to have been married in this month, and at the time of his sickness and sudden death I was adding apartments to my house for his permanent accommodation. I wish that you could have known him. At twenty-seven years the best life is only preparation. He built his foundation so large that it needed the full age of man to make evident the plan and proportions of his character. He postponed always a particular to a final and absolute success, so that his life was a silent appeal to the great and generous. But some time I shall see you and speak of him.

We want but two or three friends, but these we cannot do without, and they serve us in every thought we think. I find now I must hold faster the remaining jewels of my social belt. And of you I think much and anxiously since Mrs. Channing, amidst her delight at what she calls the happiest hour of her absence, in her acquaintance with you and your family, expresses much uneasiness respecting your untempered devotion to study. I am the more disturbed by her fears, because your letters avow a self-devotion to your work, and I know there is no gentle dullness in your temperament to counteract the mischief. I fear Nature has not inlaid fat earth enough into your texture to keep the ethereal blade from whetting it through. I write to implore you to be careful of your health. You are the property of all whom you rejoice in art and soul, and you must not deal with your body as your own.

O my friend, if you would come here and let me nurse you and pasture you in my nook of this long continent, I will thank God and you therefore morning and evening, and doubt not to give you, in a quarter of a year, sound eyes, round cheeks, and joyful spirits. My wife has been lately an invalid, but she loves you thoroughly, and hardly stores a barrel of flour or lays her new carpet without some hopeful reference to Mrs. Carlyle. And in good earnest, why cannot you come here forthwith, and deliver in lectures to the solid men of Boston the History of the French Revolution before it is published—or at least whilst it is publishing in England, and before it is published here. There is no doubt of the perfect success of such a course now that the five hundred copies of the Sartor are all sold, and read with great delight by many persons. This I suggest if you too must feel the vulgar necessity of doing; but if you will be governed by your friend, you shall come into the meadows, and rest and talk with your friend in my country pasture.

If you will come here like a noble brother, you shall have your solid day undisturbed, except at the hours of eating and walking; and as I will abstain from you myself, so I will defend you from others. I entreat Mrs. Carlyle, with my affectionate remembrances, to second me in this proposition, and not suffer the wayward man to think that in these space-destroying days a prayer from Boston, Massachusetts, is any less worthy of serious and prompt granting than one from Edinburgh or Oxford. I send you a little book I have just now published, as an entering wedge, I hope, for something more worthy and significant. This is only a naming of topics on which I would gladly speak and gladlier hear. I am mortified to learn the ill fate of my former packet containing the Sartor and Dr. Channing’s work. My mercantile friend is vexed, for he says accurate orders were given to send it as a packet, not as a letter. I shall endeavor before despatching [sic] this sheet to obtain another copy of our American edition.

I wish I could come to you instead of sending this sheet of paper. I think I should persuade you to get into a ship this Autumn, quit all study for a time, and follow the setting sun. I have many, many things to learn of you. How melancholy to think how much we need confession! […] Yet the great truths are always at hand, and all the tragedy of individual life is separated how thinly from that universal nature which obliterates all ranks, all evils, all individualities. How little of you is in your will! Above your will how intimately are you related to all of us! In God we meet. Therein we are, thence we descend upon Time and these infinitesimal facts of Christendom, and Trade, and England Old and New. Wake the soul now drunk with a sleep, and we overleap at a bound the obstructions, the griefs, the mistakes, of years, and the air we breathe is so vital that the Past serves to contribute nothing to the result.

I read Goethe, and now lately the posthumous volumes, with a great interest. A friend of mine who studies his life with care would gladly know what records there are of his first ten years after his settlement at Weimar, and what Books there are in Germany about him beside what Mrs. Austin has collected and Heine. Can you tell me? Write me of your health, or else come.

Yours ever,

R.W. Emerson.

P.S. I learn that an acquaintance is going to England, so send the packet by him.

+

FURTHER READING

For Emerson’s review of Carlyle’s Past and Present (1843), click here.

For more on the tragic, early death Emerson’s brother, Charles, click here.

For more on the Emerson/Carlyle relationship, click here and here.

For their complete correspondence, click here.