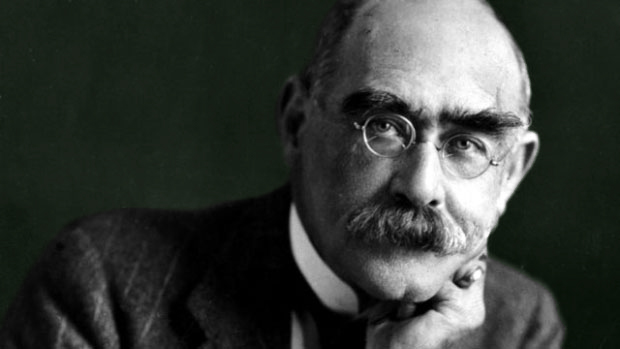

In 1918, Rudyard Kipling received copies of advertisements placed in trade journals that carried passages from his poems, the intention of which, he was informed, was to “help the patriotic feeling among readers.”

TO J.H.C. BROOKING

January 1918, Sussex

Dear Mr Brooking,

I have been away from home, or I should have answered your letter, with enclosed series of your firm’s advertisements, before this.

I have had some experience in the unauthorized use of my verses, but I confess that what you have done is outside all my experience. I send you with this a copy of a letter from my lawyers to me which will show you to what extent you have infringed the law of copyright. You have been using my verses in order to draw attention to your firm’s goods. Obviously, unless you believed that people would have been attracted by the verses you would not have used them. I do not know how long it has taken your firm to make, perfect and popularize its output. It has cost me close on thirty-five years to build up the goodwill and connection of my business which you have used for your firm’s advantage, without my knowledge or consent.

To reverse the situation for a moment, conceive what my position would be if it came to your firm’s knowledge that, for over a year, I had been appropriating portions of their apparatus and presenting them gratis to the public in order to help the sale of my books. It has been repeatedly established that an author’s writings cannot be used for the purposes of advertisement without his sanction. Were this not so, you can easily see that a man’s work might be used to forward most objectionable purposes.

But I hope you will agree with me that you are lucky in having chosen me for the subject of what, in your own interest, I trust is your first experiment in this line. I say this because the letter in which you refer to having “taken my name in vain” (i.e. taken my property) and enclose the advertisements which establish the case against yourself, seems to prove that you acted in good faith—perhaps on your own responsibility—and without knowledge of what you were laying your firm open to. This makes me less inclined to move against your firm till I have written to ask you if you can see your way to give me an undertaking that you will not use any further extracts from my writings in your firm’s advertisements.[1]

Yours faithfully,

Rudyard Kipling

+

FOOTNOTES

[1] Apparently, Mr. Brooking had no idea Kipling would take such offense to the unauthorized use of his words. He replied that he was “greatly surprised” by Kipling’s response, and agreed to desist. Kipling then allowed the firm to print extracts from his verses without any accompanying advertising, “but not more than two-thirds of any set of verses.”