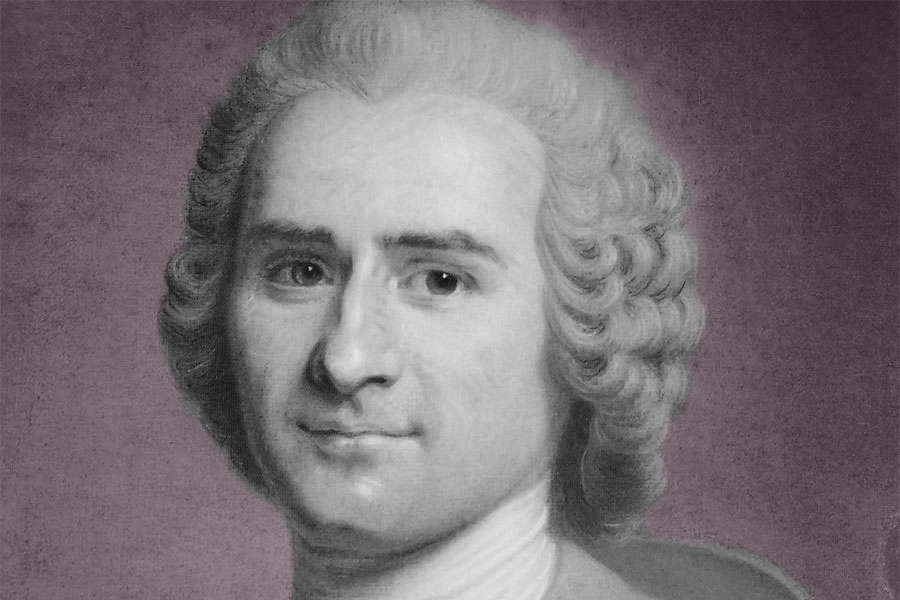

Jean-Jacques Rousseau consoles the Prince of Württemberg following the Seven Years War, extolling independence of thought and advising him to turn away from the world of public acclaim to better cultivate his family life.

Môtiers

April 17 1764

Lament not your ill fortunes, Prince, for since they are the outcome of your courage and your virtues, they are also the instrument of your glory and your happiness. To have conquered Frederick would no doubt have been a fine stroke, but to conquer in one’s own heart the prejudices and passions that subjugate the conquerors as well as other men is finer still; and tell the truth, how many victorious battles could have given you, in the opinion of men, what an hour’s delight in the pleasures of conjugal love and paternal affection gives you in the depth of your own heart? If your victories would have meant some real good for men (which seems to me very doubtful, for what does it matter to the several nations which one of you loses or wins?), you would have mistaken the real goods for yourself, and seduced by public acclaim, you would have placed your happiness for the future only in the judgments of others. You have learned to find it in yourself, to be master of it, to enjoy it in spite of everything, and you have conquered it, so to speak: that is the best conquest to make.

The times of glory are as intoxicating in my calling as in yours. I do not know if they have gone to my head, but they have often made me sick at heart, and it is quite difficult for a warrior in the midst of triumphs not to feel the same affliction, for if the laurels of heroes are more brilliant, the cultivation of them is also more painful, more enslaving, and often one is made to pay dearly for them.

The manner of living I have chosen, isolated and unpretentious, which makes me practically solitary on the earth, has put me into a position to observe and compare all conditions of men, from peasants to nobles. I have easily been able to discount appearances, for I have been everywhere admitted into social intercourse and even familiarity. I have, to speak thus, incarnated myself in all stations of society in order to study them well. I have seen their sentiments, their pleasures, their desires, their inner modes of existence. I have always observed that those who knew how to make their situation not the most magnificent but the most independent were those nearest to all the felicity permitted to man; that the free sentiments they cultivated, such as love, friendship, were relished in a wholly different way from those arising out of the forced relationship created by station and rank; and finally that the affections which had to do with persons and were choices of the heart were infinitely sweeter than those relating to things and determined by fortune.

On such a principle it has seemed to me from the very first letters with which you honoured me (and all the others confirm this judgment), that you have made the greatest strides toward the attainment of happiness, that to transform oneself from a prince and a general into father, a husband, a veritable man, was not to enter upon privations but joys… that you might have some troubles, because everyone does, but that if anyone in the world came near to true happiness in his situation and affections, it must be yourself, and that on occasion of the misfortune which led you to this simple and desirable state you could have said as Themistocles did ‘We should perish if we had not perished.’ There, Prince, you have my way of thinking about your situation present and past. If I am mistaken, do not undeceive me.

J.J.R.

FURTHER READING

For a letter from Rousseau to Voltaire, featuring quite different sentiments, read here

Likewise, a delightfully-photographed chronology of Rousseau’s refuge in Switzerland, and his time spent in Môtiers, can be found here