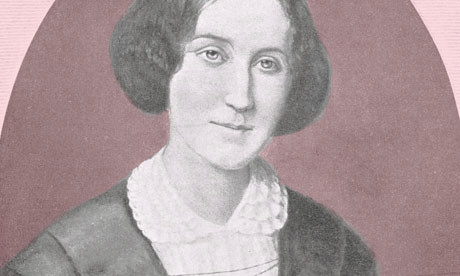

Mary Anne Evans, best known by her pen name George Eliot, developed a romantic attachment to John Walter Cross when they began work together on a translation of Dante’s Divina Commedia. Cross worked as Eliot’s accountant while she lived with George Henry Lewes in a long-term unsanctified relationship, scandalous for its time. Eighteen months after Lewes’s death, the sixty-year-old Eliot would marry Cross, twenty years her junior.

Little is known about the intimacies of their marriage; biographers have speculated that it was never consummated. In the following letter, addressed seven months before the nuptial ceremony, Eliot is quick to emphasize the superiority of her intellect over her partner’s. The quote from the Aenied, which translates as “Woman is ever a fickle and changing thing,” also appears in Chapter 6 of Eliot’s Middlemarch, when Mr. Brooke tells Mrs. Cadwallader that “[women] are not thinkers.” In a reversal of her penned literary situation, Eliot is not only a thinker but the thinker, leaving Cross to affairs of the “manly heart.” She signs with the name Beatrice, that passive muse of Dante’s beatitudes, perhaps in ironic gesture to the female role she herself defied.

[The Heights, Witley, October 16 1879]

Best and loving one—the sun it shines so cold, so cold, when there are no eyes to look love on me. I cannot bear to sadden one moment when we are together, but wenn Du bist nicht da I have often a bad time. It is a solemn time, dearest. And why should I complain if it is a painful time? What I call my pain is almost a joy seen in the wide array of the world’s cruel suffering. Thou seest I am grumbling today—got a chill yesterday and have a headache. All which, as a wise doctor would say, is not of the least consequence, my dear Madame.

Through everything else, dear tender one, there is the blessing of trusting in thy goodness. Though dost not know anything of verbs in Hiphil and Hophal or the history of metaphysics or the position of Kepler in science, but thou knowest best things of another sort, such as belong to the manly heart—secrets of lovingness and rectitude. O I am flattering. Consider what thou wast a little time ago in pantaloons and black hair…

…Why should I compliment myself at the end of my letter and say that I am faithful, loving, more anxious for thy life than mine? I will run no risks of being ‘inexact’—so I will only say ‘varium et mutabile semper’ but at this particular moment thy tender

Beatrice

From Selections from George Eliot’s Letters. Edited by Gordon S. Haight. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985. pp. 517-518.

FURTHER READING

Details of Cross’s suicide attempt, made during the couple’s Venetian honeymoon.

Review of the latest “salt and spice” Eliot biography.

Beatric