Here, James Dickey writes to his son Christopher, who was in El Salvador working as a foreign correspondent for The Washington Post. Dickey writes in a state of worry after Olivier Rebbot, a French photographer covering the Salvadoran civil war for Newsweek, was shot by a sniper. Rebbot died a month later.

My dear son,

It has been years since I have written you an actual letter, for we usually talk on the phone or face to face, but I had the impulse to write you this one, particularly after Carol’s phone call of the other night and the news of the events down there. Last night, reporting the wounding of the Newsweek guy Rebbot, John Chancellor concluded with saying, “…and this makes El Salvador the most dangerous country in the world for foreign journalists.” Well, I thought with numbness but also some other emotion too, I’ve got a son down there, and he is a journalist, and he is certainly foreign; he never grew up in El Salvador in his life; he is the gringo of gringos, there in his flak vest and talent, with his uncompromising blue eyes and steadiness of purpose, with his very great courage, and with all those memories that I have, going back through many years, not only to the beginning of him but to the beginning of me, and before that too, back to the caves and before, to the creation of the life-chemicals themselves, which the physicist Urey, who died the other day, said were fused and/or created by lightning. All that, I thought, and that, and this guy who is myself as well as my son—the latter by far the more prominent and better of the two—is down there among all that high-speed random lead, and there’s nothing I can do about it except to pray that none of it hits him, and to pray especially that none of it even comes close. Since you told me about your girl stringer in Salvador, I have been wondering whether the woman blown up by the Claymore last night might be the same, and whether in consequence it might have been you in the car instead of her. How may I resolve this?

The most dreadful thing about war is the unexpectedness with which things happen. Given any chance at all, any forewarning, I have strong hopes for your safety, and these may even be reasonable, based on your ability to read a situation, your resourcefulness and your coolness, but the trouble is that some of the time there is no way to assess all the elements. For example, Rebbot was hit by a sniper, flak-vest and all, and this means that someone—someone hidden—was shooting specifically at him, and that bothers me. It bothers me particularly because I can’t give you any advice which might enable you to deal with it, except to say that when there is firing—any firing, no matter how distant—to stay low, and take whatever cover there is.

You needn’t answer this at any length, or even at all if you don’t have time or if things are too hectic; I just wanted to write it to tell you how very precious you are to me, and how proud I am of you and of the stand you are making in that war. You are in a crucial area not only of geography and politics but of history. Hemingway or Malraux or Tolstoy or anybody else was never more central to a crucial situation than you are now. When you come out of this, a legend will come with you: the legend of what you write, which will be also what you have lived and what you have dared and surmounted and made possible in the way of understanding. That is heroic, son; nothing else. Believe me, my blood and your mother’s must be good, for it is in you and had produced you. Just don’t spill any of it. Keep your head down and your vest on; keep your cool and your good sense, and your talent will do the rest.

Things are well here, though many projects must constantly be attended to. Kevin was accepted into medical school at Charleston, we are back in the house at Litchfield, and Debba and I are feeling okay. I am on sabbatical, but with the work-load life is more strenuous than when I had the relief—maybe comic relief—of teaching. Stephen spender is filling in for me this semester, and seems to like it here well enough.

I’ll sign off, and send more love and pride.

Yours,

Dad

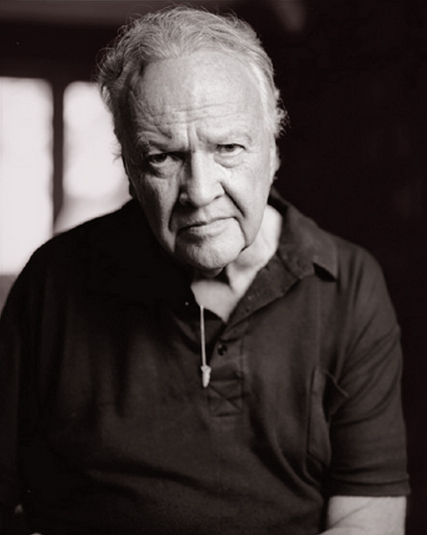

P.S. I enclose a picture of me + Tucky the Hunter on that illustrious occasion when we went after Bigfoot, here in the back yard.

From The One Voice of James Dickey: His Letters and Life, 1970-1997. Dickey, James, and Gordon Van Ness. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2005.