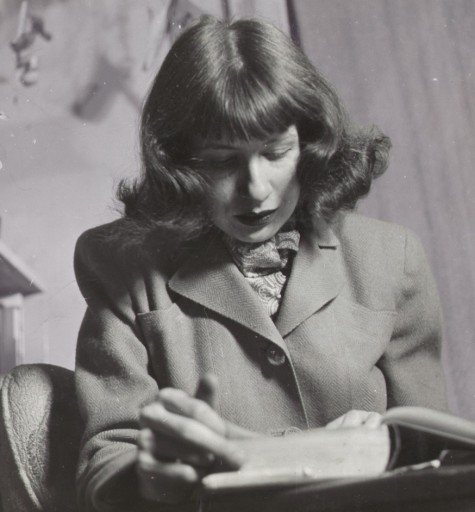

In 1953, Amy Clampitt worked as a reference librarian at the Audubon Society in New York. Here, Clampitt writes to her younger brother Philip about spending days in bed with a cold reading The Natural History of Selborne, and becoming fascinated by the Sussex tortoise, gleaning from it lessons about enthusiasm.

Dear Philip—

Your letter arrived on a day when I had given up coping with broken boilers and fifty-degree temperatures at the new Audubon house and gone to bed with a galloping sore throat. It presently turned into quite a conventional cold, thereby upsetting my theory about seasonal immunities, and since the boilers still weren’t fixed I spent four days in bed. I almost said four wonderful days, but they weren’t really, in fact I was so disinclined to get up that I began to wonder uneasily whether I was ever going to; the wonderful thing was that when I did totteringly pull myself together in the middle of Friday afternoon the cold was practically gone. The Kleenex supply had run out, I just remember—that was really why I had to get up. Matthias had meanwhile very kindly gone to the grocery store for me, and on the day before another friend of mine had dropped in and shared a hot toddy—whiskey and lemon juice with boiling water and two cloves—which didn’t do me a bit of good.

But you must be quite bored with bedridden people and their symptoms by this time. I didn’t mean to go into so much detail about the fascinating common cold. The one thing I did that isn’t usually done was to discover Gilbert White. Maybe you know about him—the eighteenth-century Englishman, a clergyman evidently, who wrote The Natural History of Selborne. I read the whole thing, and when I had finished I had the rare feeling of being sorry that there wasn’t any more. He made it his business to note down everything like the habits of cockroaches, the rainfall, the dew, the growth of trees, and the appearances and disappearances of birds, at a time when there was still some doubt about whether migration really occurred. He never did decide for certain whether swallows and swifts actually left the country or merely hibernated somewhere or other. He had a friend who went out with a pitch-pipe and discovered, or thought he had, that all the owls hooted in B-Flat; but then one of them went down to A, so the generalization had to be abandoned. He was the most patient curious man who ever lived, I do believe, and that is his great charm. The one time he seems to [have] been even slightly inclined to pass moral judgements on animal behavior (he was always looking for explanations of why the cuckoo should lay its egg in another bird’s nest, but he never found one, though for a while he thought he had), the one creature that seems to have incensed him the least a little bit was an old tortoise, and I suppose that was because he had gotten fond of it. He saw it first in another town, where it had been living for a good while, and watched it digging in for the winter, with the speed, he said, of the hour hand on a clock.

Eventually, after a series of references to it, he notes that “the old Sussex tortoise is now become my property.” He dug it up before the end of the hibernation season, carried it back to Selborne, and dug it into his own garden, where he noted that on one day of unseasonable warmth, in February or March, it came out for a while but then retired underground. He noticed that it was as fussy as an old lady about being caught in the rain, and would go for cover though heaven knew that it was as well protected already as one would suppose necessary. And then he exploded that it did seem odd that a creature so torpidly oblivious to delight of any kind should be permitted to drag out so long an existence on earth. Later on he seems to have made amends by noting a few more positive qualities, such as that it did have sense enough to keep from falling down a well when it came to the edge of it. Well, you can see that I have been pretty much obsessed with that tortoise ever since. I have already told one person whom I quite liked but found somewhat exasperating that he was an old Sussex tortoise. The upshot was that I managed to get him to unearth some enthusiasms—Adlai Stevenson, and the ballet, and some novel by John O’Hara, and some other girl who hasn’t anything to say. Of course the last exasperated me all over again, but that was no doubt what I deserved. Anyhow, for the time being “Don’t be an old Sussex tortoise” seems to be my rallying cry. Why are people so afraid of being enthusiastic? I don’t think it’s so much laziness as the fear of turning out to be wrong. But who knows what is right anyway? If one only feels the right things one might as well not feel anything. Of course one usually is wrong. I’ve been being enthusiastic about getting knocked down and proved wrong for some time now, so that I’m practically used to it.

Now what all this had to do with anything I don’t quite know. I think it was brought on by your almost confessing to envy me for enjoying Philosophy in a New Key and then taking it back, almost and all. I don’t see anything wrong with that—it’s probably healthy, and besides, at your age I would have found the whole thing impenetrable. I’ve forgotten the logical framework already, in fact I had before I finished the book. What I understood I understood through things that had affected me, and I’ve had ten more years to be affected in than you have. You have a far better brain than I do, and you use it. What needs paying attention to now is your feelings, which are undoubtedly there somewhere though you seem to do a wonderful job of traveling miles in order to circumvent them. Does this make you mad? It ought to.

Well, here you are, twenty-three years old tomorrow. I’m late with birthday wishes, but then I always am. These are about the queerest I ever sent anybody, but you see it’s all on account of that old Sussex tortoise.

Love,

Amy

From Love, Amy: The Selected Letters of Amy Clampitt. Clampitt, Amy, and Willard Spiegelman. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.