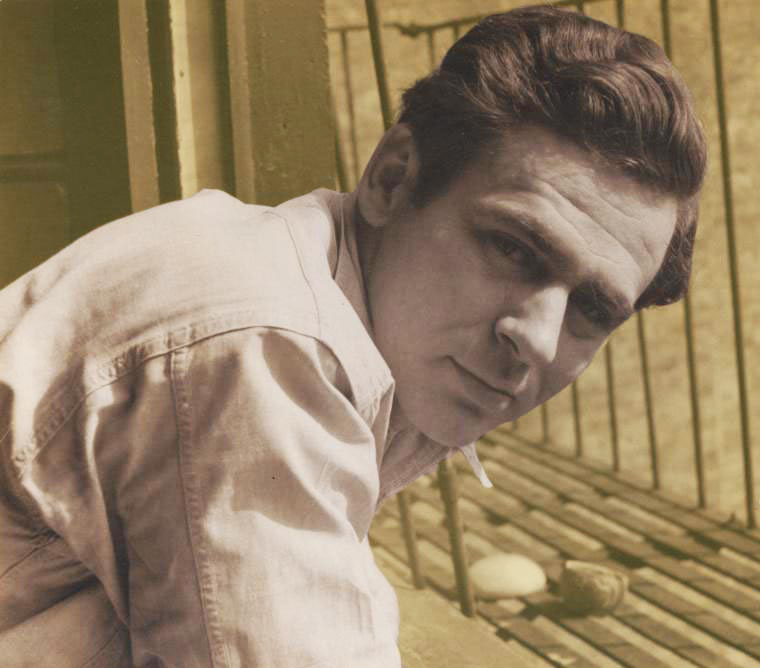

Shortly after the death of his father, James Agee arrived at St. Andrew’s School at the tender age of ten years old. One of his first and greatest friendships began almost immediately with Father Flye, who had only arrived the year before. At sixteen, Agee (who went by the name of Rufus) traveled with Father Flye to France after studying French for years together. It was his first and only trip to Europe. Agee went on to write film criticism for The Nation which he refers to below. In this letter, Agee discusses his thoughts on imminent anti-discrimination legislation. In 1945, New York State was the first state to put such laws into effect, and established the New York State Commission Against Discrimination for enforcement. In a New York City taxicab, Agee died of a heart attack at forty-five. Two years later, his novel, A Death in the Family, was published and won the Pulitzer Prize.

[New York City]

[May 15, 1945]

Tuesday afternoon

Dear Father:

Thank you for your letter. This is another spare-moment reply. I’m in a bad temper (heat, rush, behind on NATION work, still worse behind on work of my own, hopelessness of ever getting free time, hopelessness of ever using it well if I do) of which I must warn you; I hope I won’t take any of it out on your or in this note. I’m partly worried about that because the main thing that pricks up my ears, or the hair along my back, in your letter, as probably you can imagine, is what you say of the anti-discrimination legislation. The things you object to, I object to also; I intensely dislike coercion of that or any other kind, and it is all a part of a much larger texture of coercions which are becoming more and more assured as necessary of anyhow as inevitable [sic] but with at least equal intensity I dislike the forms of discrimination which this kind of legislation is trying to combat. There are very few ways of combatting it, and on the whole I am afraid they are worse than useless; but such as the ways are, and poor as they are, I am for them. The surprising part about them, too, is that they seem to work. In the Army, in those few instances where Whites and Negroes have really been flung together rather than just torturingly and stupidly rubbed together, the difficulties which were expected to make their good functioning virtually impossible, were dissolved quite quickly. In subways here, and at civil service desks, Negroes are much used—used enough that it is for that matter a little silly and self-conscious—but it is working well; people accept without strain or affectation what many of them must have supposed in absence of the fact would be difficult or impossible to accept. A thing I feel you overlook in your objection to it is the general though not universal fact that people are, through their race or religion (or sex) discriminated against not just in those ways alone but economically; and very severely in that respect. The whole complex of those preferences and prejudices the right to whose indulgence you are defending, works to help keep Negroes (for instance) by the millions, impoverished, and in the case of Jews, where it is economically much more jagged, works towards keeping them clannish, interdependent and predatory. That seems very important to me. But even if it weren’t; if nobody or group suffered economically through it; I would object just as strongly. One can do nothing in the long run to force or persuade a Jew-hater to like Jews or to cease generalizing (which is more to the point); but I feel no more like defending him through the law than I do like making laws to protect those who like to seduce little girls with candybars [sic].

Each of us really is talking about what we regard as a “right.” You feel strongly about the right of a man to hire or not hire whom he pleases. So do I. But I also feel that any human being has the right not to be discriminated against in order to indulge somebody’s right to hate, for instance, Jews or Negroes. I feel it the more strongly because I don’t regard that right to hate as a right at all but as a deadly wrong. That the hatred exists does not justify its existence, any more than the existence in each or most of us of cruelty or vengefulness justifies cruelty or vengefulness. I realize that the emotional ramifications and depths behind this kind of dislike or fear are all but infinite and are far beyond the personal reach or responsibility of most who feel it (Whites in the South about Negroes I think of); and that such legislation is headed for trouble, as well as for the traduction of certain kinds of rights. Well it may be of minor importance or difference, but I would rather see change and trouble arise as little bloodily and brutally as possible; and though such methods as this will certainly bring about some, I am sure that infinitely worse will come if they are not used. When you watch it in its potentialities it is of course fully tragic and hopeless; and the temptation is strong to prefer the relative tranquility of the present of past. But nothing on earth is going to stop the change; just as nothing on earth is going to bring it through to any good. And the question between which is right, or more greatly right, seems very little question at all if any. (I mean that one seems far more greatly right.)…

R.

From Letters of James Agee to Father Flye. Edited by James Harold Flye. Brooklyn: Melville House Publishing, 2014. pp. 122-4.

FURTHER READING

James Agee claimed to have written Knoxville: Summer of 1915 in less than ninety minutes.

The American Prospect published a biographical essay on Agee before he was famous.

Read an excerpt on Anti-discrimination legislation action in New York state.