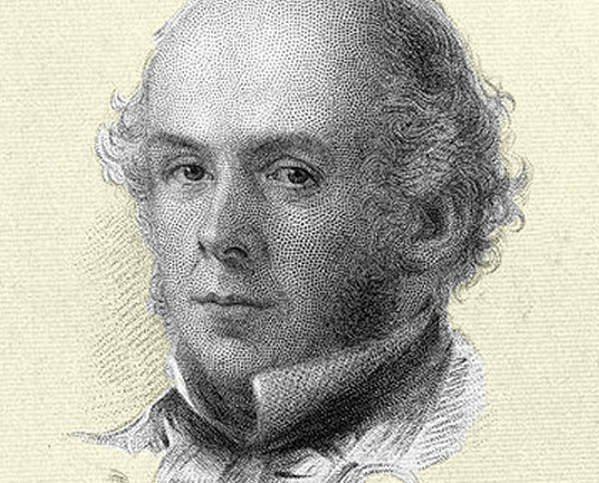

Arthur Hugh Clough, English poet and onetime assistant to Florence Nightingale, writes to Mary Shore Smith, whom he would later go on to marry, about the dynamics of quotidian religion and the peculiarly egalitarian economic landscape of mid 19th century Massachusetts.

March 15, 1853

My dear child,

About being religious–the only way to become really religious is to enter into those relations and those actualities of life which demand and create religion. So have good hope. You will do that one day I trust, will you not?–Meantime the utmost you can be expected to do, is to feel your own inexperience…

It is agreeable to find here how much more numerous the chances of employment are; every week brings a new–disappointment, shall I say?–which is very encouraging. Dear Blanche, I don’t think you would really mind about the poverty, such as it is here. What is it you most apprehend in it–having to do drudgery? I don’t see that there need be much of that. It is very common here you see for Mrs. so-and-so who has small means, to take in ‘a boarder’ and that of course more than doubles the annoyance, because boarder’s don’t consider. The servant I have told you about–I think one English girl and a boy would be quite enough. People don’t the least despise one for being poor, here in Cambridge at any rate, and I recommend them not. Here are two Miss Wheatons and their Mother living here. The Father, now dead, was American Minister for many years at Berlin and Copenhagen and I think for a little while at Paris;–and now one Miss Wheaton teaches French and the other Music, and they live in a house of $250 rent. My opinion is that the true position in this country is that of comparative poverty. No sort of real superiority, of breeding or anything, attaches as it does in England, to the rich. The poor man can get his children educated at the public schools to which the rich children go also,–for nothing,– prepared for College even. –And very few people indeed are so rich by patrimony as not to be in business.

Dearest child–Here I am back from the Post; which brings a letter from Margaret my brother’s wife…Also one from Carlyle, which I suppose I must send you by the Collins on Saturday. It is rather puzzling. I confess I would almost rather stay here–but if return falls in my way, I must take it…

Lord Granville promises Lady Ashburton ‘I will propose’ me ‘to the British and Foreign Society as soon as a vacancy occurs in their Inspectorships’; however there are but three–Morell, Matt Arnold, and Bonstead, so before any opening occurs, the Administration may be an Opposition–

So much for that.–

What with these letter, or the horrid dreadful cold–thermometer at 12 and wild, blowing, cutting wind–I have not got on so well; for I also–I should say,– went to the Longfellows’ and dined 1 1/2 – 5. However I have done 18 pages, so I shall manage the 20 at any rate. Tomorrow morning I must go in with this. –O dear, it is most disagreeably cold; one fancied it was all over. But it won’t last they say. I hope not indeed.

As for these English hopes I think little of them–and mean to think less. –There seems to me to be no liklihood of any vacancy. Nor do I by any means feel sure that we should be happier there than here…

Arthur Hugh Clough

+