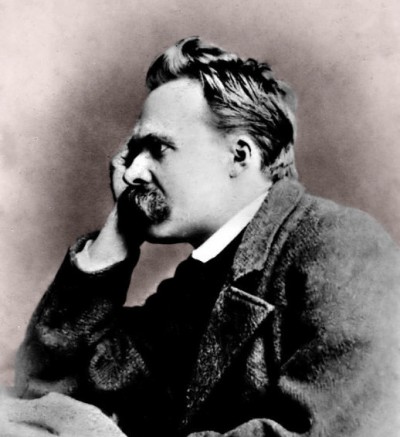

Once an avid supporter of Richard Wagner and his compositions, Friedrich Nietzsche began to distance himself from the composer after the 1876 Bayreuth Festival, an annual music festival that showcased the works of Wagner. Nietzsche, annoyed by the cultural and religious sentiments of the “Bayreuth circle” he had once been a proud member of, gave up his Gellertstrasse apartment and fled from his social obligations, despite his sister Elisabeth’s protests. At Interlaken, he completed part of “The Plowshare,” which became his book Human, All Too Human. In turn, Wagner published “Publicum und Popularität,” or “Audience and Popularity,” one month after this letter was sent to their mutual friend Mathilde Maier. The essay went against Human, All Too Human and appeared only a few months after the book’s publication.

Interlaken, July 15, 1878

Verehrtestes Fräulein:

It cannot be helped—I must bring distress to all my friends by declaring at last how I myself have got over distress. That metaphysical befogging of all that is true and simple, the pitting of reason against reason, which sees every particular as a marvel and an absurdity; this matched by a baroque art of overexcitement and glorified extravagance—I mean the art of Wagner; both these things finally made me more and more ill, and practically alienated me from my good temperament and my own aptitude. I wish that you could now feel as I do, how it is to live, as I do now, in such pure mountain air, in such a gentle mood vis-à-vis people still inhabiting the haze of the valleys, more than ever dedicated, as I am, to all that is good and robust, so much closer to the Greeks than ever before; how I now live my aspiration to wisdom, down to the smallest detail, whereas earlier I only revered and idolized the wise—briefly, if you could only know how it feels to have known this change and this crisis, then you could not avoid wishing to have such an experience yourself.

I became fully aware of this at Bayreuth that summer [1876]. I fled, after the first performances which I attended, fled into the mountains, and there, in a small woodland village, I wrote the first draft, about one-third of my book, then entitled “The Plowshare.” Then I returned to Bayreuth, on my sister’s wishes, and had enough inner composure to endure the almost unendurable—in silence too, telling nothing to anyone. Now I have shaken off what is extraneous to me: people, friends and enemies, habits, comforts, books; I live in solitude—years of it, if needs be—until once more, ripened and complete as a philosopher of life, I may associate with people (and then probably be obliged to do so).

Can you remain, in spite of everything, as kindly disposed to me as you were—or, rather, will you be able to do so? You can see that I have become so candid that I can endure only human relationships which are absolutely genuine. I avoid half-friendships and especially partisan associations; I want no adherents. May every man (and woman) be his own adherent only.

Your cordially devoted and grateful F.N.

From Selected Letters of Friedrich Nietzsche. Edited by Christopher Middleton. Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 1996. pp 167-168.

FURTHER READING

Watch a BBC documentary about Nietzsche and his exploration of moral and religious certainties.

Read about changes in perceptions of Wagner’s music in the 21st century, with commentary from Nietzsche included.