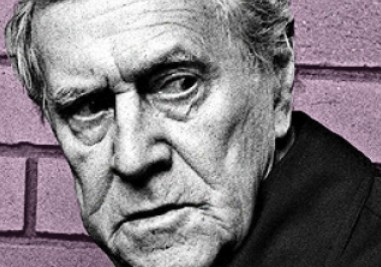

Australian novelist and 1973 Nobel laureate Patrick White writes to his cousin, the sculptor Peggy Garland, giving her an update on his doings and his recent “discovery” of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Dogwoods, 15.viii.51

My ‘acedia’ continues. Funnily enough this was diagnosed by an Anglican priest who stayed with us a couple of years ago. There are moments when I do take interest in a book I have in my head, and of which I wrote a certain amount while the Poles were with us, then I succumb to the feeling of: What is the use? Since the war I cannot find any point, see any future, love my fellow men; I have gone quite sour—and it is not possible, in that condition, to be a novelist, for he does deal in human beings.

While I was in bed lately I succeeded in reading what is an awful lot, for me, now, and discovered Scott Fitzgerald, of whom I had heard vaguely, but never met. You must acquaint yourself, if you haven’t done so already. The Great Gatsby is in the Penguins, a work of art out of unexpected material—rich Long Islanders and phoney New Yorkers—but read it and see. Then I read his Tender is the Night, not in the same class as a whole, rather too much virtuosity, but vastly entertaining, and having flashes of wisdom. I am still glowing from my discovery. It is so good, when you think you have left no stone unturned, to find that there is one.

In this same spasm of reading, I read an excellent book on the ancient Greeks by H. D. F. Kitto, a crazy, but true book on Modern Greece by Henry Miller called The Colossus of Maroussi, and re-read Davidson’s excellent biography of Edward Lear, and Symons’ brilliant excavation of the nauseating Corvo. Finally, I re-read the two books that have meant more to me than anything in the last ten years, George Moore’s Evelyn Innes and Sister Teresa. Do you know these two? They are out of print. I am tempted to send them to you, as I think you would like them as much as I do, but on second thought, I don’t feel I could part with them…

The garden, in parts, is looking much the worse for a very frosty winter, in others there are clouds of prunus and cherry, and thickets of cerise and pink japonica. And I am particularly pleased with a bush of gorse, the yellowest of yellow in flowers, as if someone had taken a saucepan of scrambled egg and flung it at a bush of thorns. Some day, God willing, the garden will be a sight to see, and I look forward to that very definitely, even though we be in tatters ourselves and the house collapsed.

I have Parsifal in the background on the wireless, and it is a struggle to write. I don’t really like Wagner, do you? There are seductive bits riding here and there, but I have to force myself to most of it. I feel that unless one is German, one has to be of that period when to like Wagner was to revolt against the conventions, really to enjoy it. (Floundering, Wagnerian sentence, but perhaps you can unravel it.)…

No more can I write. Parsifal has become a nest of snakes.

I hope I have not kept the photographs too long. Some day I must try to take Dogwoods and avoid turning out a suburban box surrounded by puny shrubs quite unlike the magnificent ones of fact—or imagination.

Yours,

Patrick.

From Patrick White: Letters. Edited by David Marr. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994. 688 pp.

FURTHER READING

Read the New York Times‘ review of Patrick White’s posthumously published novel The Hanging Garden here.

Read an essay on White’s “disappearance from England’s cultural consciousness” from the English culture webzine The Quietus here.