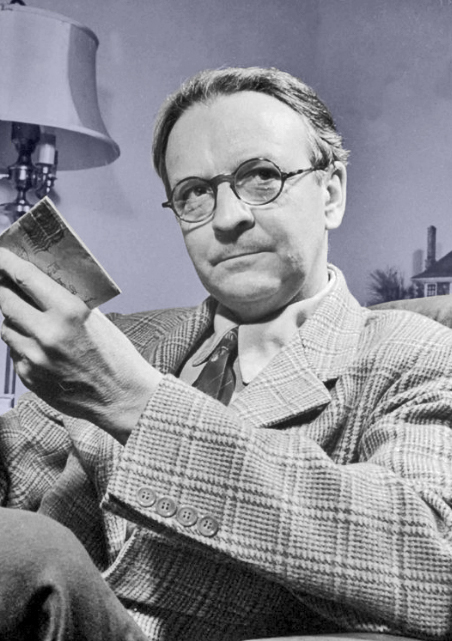

“No highbrow writer need dread being caught with a Chandler whodunit in hand,” a reviewer once said. Here, Raymond Chandler writes to Bernice Baumgarten, an editor at Brandt and Brandt Literary Agency, concerning his recently completed novel. Houghton Mifflin published The Long Goodbye in 1953. Below, Chandler reflects on the creative problems presented by the form of the mystery novel.

To Bernice Baumgarten

6005 Camino de la Costa

La Jolla, California

May 14 1952

Dear Bernice:

I’m sending you today, probably by air express, a draft of a story which I have called The Long Goodbye. It runs 92,000 words. I’d be happy to have your comments and objections and so on. I haven’t even read the thing, except to make a few corrections and check a number of details that my secretary queried. So I am not sending you any opinion on the opus. You may find it slow going.

It has been clear to me for some time that what is largely boring about mystery stories, at least on a literate plane, is that the characters get lost about a third of the way through. Often the opening, the mis en scene, the establishment of the background, is very good. Then the plot thickens and the people become mere names. A very good example of this is a current work called Reclining Figure by my friend Harry Kurnitz (Marco Page.) It begins so well, but in the end it is the same old hash. Well, what can you do to avoid this? You can write constant action and that is fine if you really enjoy it. But alas, one grows up, one becomes complicated and unsure, one becomes interested in moral dilemmas, rather than who smacked who on the head. And at that point perhaps one should retire and leave the field to younger and more simple men. I don’t necessarily mean writers of comic books like Mickey Spillane.

Anyhow I wrote this as I wanted to because I can do that now. I didn’t care whether the mystery was fairly obvious, but I cared about the people, about this strange corrupt world we live in, and how any man who tried to be honest looks in the end either sentimental or plain foolish. Enough of that. There are more practical reasons. You write in a style that has been imitated, even plagiarized, to the point where you begin to look as if you were imitating your imitators. So you have to go where they can’t follow you. The danger is that the reader won’t either.

Yours ever,

Ray

From Letters of Raymond Chandler. Edited by Frank MacShane. New York: Colombia University Press, 1981. pp. 314-5.

FURTHER READING

Look at the only known photograph of Raymond Chandler and his wife, Cissy, from 1952.

Read Raymond Chandler’s ten commandments for writing mysteries.

Check out some of the novel covers for Mickey Spillane’s mysteries (mentioned above).