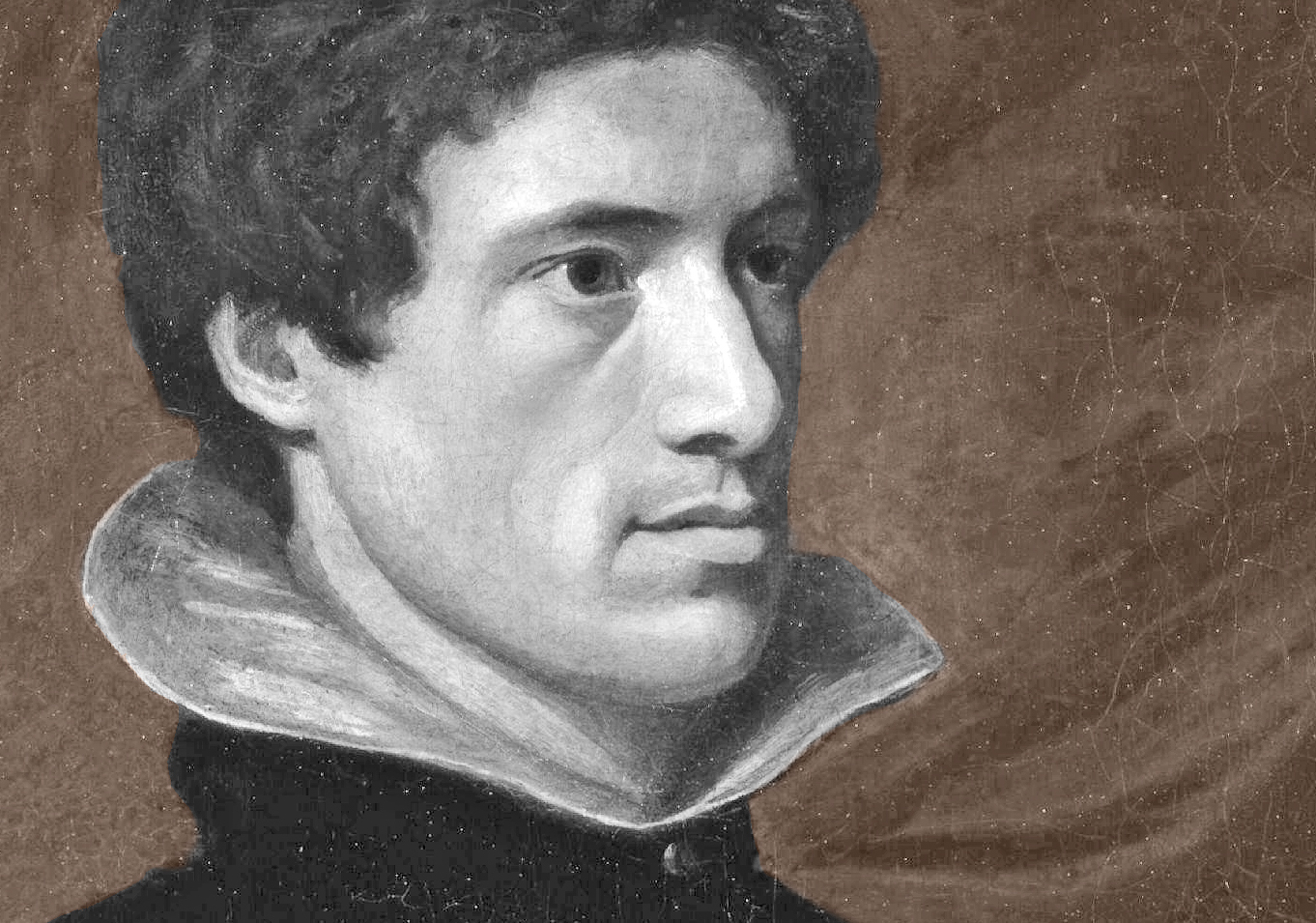

Charles Lamb and Samuel Coleridge met as schoolboys and remained close friends until the latter’s death in 1834. Below, Lamb writes to Coleridge upon receipt of the poet’s reworking of Robert Southey’s epic poem, “Joan of Arc,” noting “a certain faulty disproportion in the matter and the style…between these lines and the former ones.” He advises: “Go on with you Maid of Orleans, and be content to be second to yourself.”

To Samuel Taylor Coleridge

February, 1797

Your poem is altogether admirable: parts of it are even exquisite; in particular, your personal account of the Maid far surpasses anything of the sort in Southey. I perceived all its excellences, on a first reading, as was only struck with a certain faulty disproportion in the matter and the style, which I still think I perceive, between these lines and the former ones. I had an end in view: I wished to make you reject the poem only as being discordant with the other; and, in subservience to that end, it was politically done in me to overpass and make no mention of merit, which, could you think me capable of overlooking, might reasonably damn for ever in your judgment all pretensions, in me, to be critical. There—I will be judged by Lloyd, whether I have not made a very handsome recantation. I was in the case of a man whose friend has asked him his opinion of a certain young lady. The deluded wight gives judgment against her in toto—doesn’t like her face, her walk, her manners; finds fault with her eyebrows; can see no wit in her. His friend looks blank; he begins to smell a rat; wind veers about; he acknowledges her good sense, her judgment in dress, a certain simplicity of manners and honesty of heart, something too in her manners which gains upon you after a short acquaintance; and then her accurate pronunciation of the French language, and a pretty uncultivated taste in drawing. The reconciled gentleman smiles applause, squeezes him by the hand, and hopes he will do him the honour of taking a bit of dinner with Mrs. —– and him,–a plain family dinner—some day next week; “for, I suppose, you never heard we were married. I’m glad to see you like my wife, however; you’ll come and see her, ha?” Now am I too proud to retract entirely? Yet I do perceive I am in some sort straitened. You are manifestly wedded to this poem; and what fancy has joined let no man separate. I turn me to the Joan of Arc, second book.

The solemn openings of it are with sounds which, Lloyd would say, “are silence to the mind.” The deep preluding strains are fitted to initiate the mind, with a pleasing awe, into the sublimest mysteries of theory concerning man’s nature, and his noblest destination—the philosophy of a first cause—of subordinate agents in creation superior to man—the subserviency of pagan worship and pagan faith to the introduction of a purer and more perfect religion, which you so elegantly describe as winning, with gradual steps, her difficult way northward from Bethabara. After all this cometh Joan, a publican’s daughter, sitting on an ale-house bench, and marking the swingings of the signboard, finding a poor man, his wife, and six children, starved to death with cold, and thence roused into a state of mind proper to receive visions, emblematical of equality; which, what the devil Joan had to with, I don’t know, or indeed with the French and American revolutions; though that needs no pardon, it is executed so nobly. After all, if you perceive no disproportion, all argument is vain: I do not so much object to parts. Again, when you talk of building your fame on these lines in preference to the Religious Musings, I cannot help conceiving of you, and of the author of that, as two different persons, and I think you a very vain man.

I have been re-reading your letter. Much of it I could dispute; but with the latter part of it, in which you compare the two Joans with respect to their predispositions for fanaticism, I, toto corde, coincide; only I think that Southey’s strength rather lies in the description of the emotions of the Maid under the weight of inspiration. These (I see no mighty difference between her describing them or your describing them), these if you only equal, the previous admirers of his poem, as is natural, will prefer his. If you surpass, prejudice will scarcely allow it, and I scarce think you will surpass, though your specimen at the conclusion (I am in earnest) I think very nigh equals them. And in an account of a fanatic or of a prophet, the description of her emotions is expected to be most highly finished. By the way, I spoke far too disparagingly of your lines, and I am ashamed to say, purposely. I should like you to specify or particularise. The story of the “Tottering Eld,” of “his eventful years all come and gone,” is too general. Why not make him a soldier, or some character, however, in which he has been witness to frequency of “cruel wrong and strange distress!” I think I should. When I laughed at the “miserable man crawling from beneath the coverture,” I wonder I did not perceive that it was a laugh of horror—such as I have laughed at Dante’s picture of the famished Ugolino. Without falsehood, I perceive an hundred beauties in your narrative. Yet I wonder you do not perceive something out-of-the-way, something unsimple and artificial in the expression, “voiced of a sad tale.” I hate made-dishes at the muses’ banquet. I believe I was wrong in most of my other objections. But surely “hailed him immortal,” adds nothing to the terror of the man’s death, which it was your business to heighten, not diminish by a phrase which takes away all terror from it. I like that line, “They closed their eyes in sleep, nor knew ‘twas death.” Indeed there is scarce a line I do not like. “Turbid ecstasy,” is surely not so good as what you had written, “troublous.” Turbid rather suits the muddy kind of inspiration which London porter confers. The versification is, throughout, to my ears unexceptionable, with no disparagement to the measure of the Religious Musings, which is exactly fitted to the thoughts.

You were building your house on a rock when you rested your fame on that poem. I can scarce bring myself to believe that I am admitted to a familiar correspondence, and all the licence of friendship, with a man who writes blank verse like Milton. Now, this is delicate flattery, indirect flattery. Go on with you Maid of Orleans, and be content to be second to yourself. I shall become a convert to it when ‘tis finished.

This afternoon I attend the funeral of my poor old aunt, who died on Thursday. I own I am thankful that the good creature has ended all her days of suffering and infirmity. She was to me the “cherisher of infancy,” and one must fall on those occasions into reflections, which it would be commonplace to enumerate, concerning death, “of chance and change, and fate in human life.” Good God, who could have foreseen all this but four months back! I had reckoned, in particular, on my aunt’s living many years; she was a very hearty old woman. But she was a mere skeleton before she died, looked more like a corpse that had lain weeks in the grave, than one fresh dead. “Truly the light is sweet, and a pleasant thing it is for the eyes to behold the sun; but if a man live many years and rejoice in them all, yet let him remember the days of darkness, for they shall be many.” Coleridge, why are we to live on after all the strength and beauty of existence is gone, when all the life of life is fled, as poor Burns expresses it? Tell Lloyd I have had thoughts of turning Quaker, and have been reading, or am rather just beginning to read, a most capital book, good thoughts in good language, William Penn’s No Cross, no Crown. I like it immensely. Unluckily I went to one of his meetings, tell him, in St. John Street, yesterday, and saw a man under all the agitations and workings of a fanatic, who believed himself under the influence of some “inevitable presence.” This cured me of Quakerism. I love it in the books of Penn and Woolman; but I detest the vanity of a man thinking he speaks by the Spirit, when what he says an ordinary man might say without all that quaking and trembling. In the midst of his inspiration (and the effects of it were most noisy) was handed into the midst of the meeting a most terrible blackguard Wapping sailor. The poor man, I believe, had rather have been in the hottest part of an engagement, for the congregation of broad-brims, together with the ravings of the prophet, were too much for his gravity, though I saw even he had delicacy enough not to laugh out. And the inspired gentleman, though his manner was so supernatural, yet neither talked nor professed to talk anything more than good sober sense, common morality, with now and then a declaration of not speaking from himself. Among other things, looking back to his childhood and early youth, he told the meeting what a graceless young dog he had been; that in his youth he had a good share of wit. Reader, if thou hadst seen the gentleman, thou wouldst have sworn that it must indeed have been many years ago, for his rueful physiognomy would have scared away the playful goddess from the meeting, where he presided, for ever. A wit! a wit! what could he mean? Lloyd, it minded me of Falkland in the Rivals, “Am I full of wit and humour? No, indeed you are not. Am I the life and soul of every company I come into? No, it cannot be said you are.” That hard-faced gentleman, a wit! Why, Nature wrote on his fanatic forehead fifty years ago, “Wit never comes, that comes to all.” I should be as scandalized at a bon mot issuing from his oracle-looking mouth, as to see Cato go down a country dance. God love you all! You are very good to submit to be pleased with reading my nothings. ‘Tis the privilege of friendship to talk nonsense, and to have her nonsense respect.—Yours ever,

C. Lamb.

+