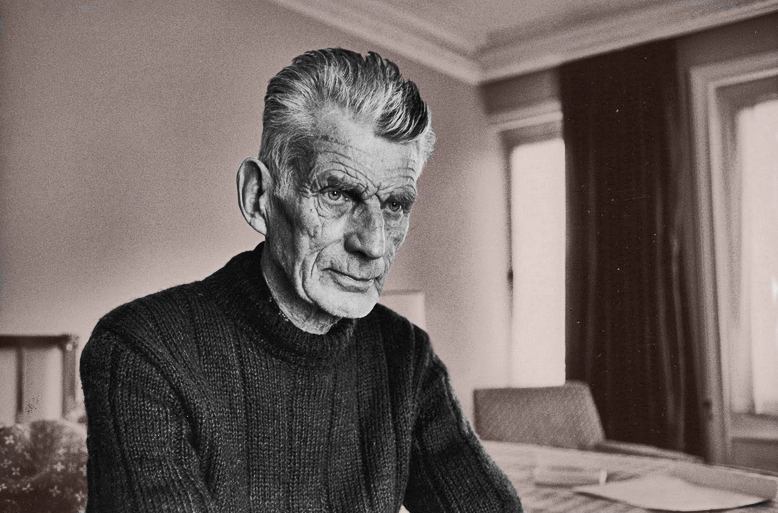

Nobel laureate Samuel Beckett writes to his aunt, Cissie Sinclair, whom he would use as inspiration for the chair-bound character Hamm in his play, Endgame. Sinclair suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, and had to stay in a wheelchair towards the end of her life. Below, he complains about the gift reception for his brother Frank’s impending marriage. The social gathering affected him so much that he also wrote of it to Thomas McGreevy (mentioned in the letter): “…it is horrible to see how society takes over at the least hint of a fresh social node of growth. neither [sic] of them wants all this hullabaloo with presents & a reception, they would both have really preferred to do without the presents if they could have been spared the fuss, & yet they submit to it.” He also encloses his poem, “Whiting”, published the following year.

Southampton, En route to South Africa

14th [August 1937]

Gresham Hotel, Dublin

dearest Cissie

[…]

I was glad to get your letter this morning. I wanted you to think of me sometimes when you had a drink. How else would I render it likely? Have many.

At least I am escaped from Cooldrinagh, the Liebespaar & Molly. All the presents pouring in, a gong this morning so terrible, the impediments of detached domesticities, the circle closing round. How much freer & libesfähiger (wenn es darauf [an]kommt!), furnished lodgings & no possessions. To be welded together with gongs and tea-trolleys, the bars against the sky, how hopeless. Is that what “home” means for all women, solid furniture & not to be overlooked, or is there another sense of home in some of them, or are there some who don’t want a home, who have had enough of that?

I saw Ilse again but she was “körperlich nicht ganz auf der Höhe”. We all know what that means. So we conversed, yes really conversed. Hans had rung up inviting her to dine. She declined. Motze [for Motz] had been out. It is something very close to disgust, nausea, & of course she feels it. Soon it will be over.

I can’t work. I have not made a pretense of working for a month. Given up even the preoccupied look & the de quoi écrire. If I got the job in Cape Town I don’t think I’d hold it for a fortnight. It would be a degradation if the terms of reference had not shriveled up. I always see the physical crisis just round the corner. It would solve perhaps the worst of what remains to be solved, clarify the problem anyway, which I suppose is the best solution we can hope for.

I had a letter from Tom by the same post as yours. He is writing about Jack Yeats, inspired apparently by some Constable exhibition & a chance remark of mine about the Watteauishness of what he has been doing lately. Every Thursday there seems to be something to prevent me going in to see him. I suppose to suggest the inorganism of the organic—all his people are mineral in the end, without possibility of being added or taken from, pure inorganic juxtapositions—but Jack Yeats does not even need to do that. The way he puts down a man’s head & a woman’s head side by side, or face to face, is terrifying, two irreducible singlenesses & the impassable immensity between. I suppose that is what gives the stillness to his pictures, as though the convention were suddenly suspended, the convention & performance of love & hate, joy & pain, giving & being given, taking & being taken. A kind of petrified insight into one’s ultimate hard irreducible inorganic singleness. All handled with the dispassionate acceptance that is beyond tragedy. I always feel Watteau to be a tragic genius, i.e. there is pity in him for the world as he sees it. But I find no pity, i.e. no tragedy in Yeats. Not even sympathy. Simply perception & dispassion. Even personally he is rather inhuman, or haven’t you felt it?

Perhaps the literary value of this letter & so if the worst comes to the worst (don’t misunderstand me) its marketable interest would be promoted by a few lines of verse. You may find them trivial & unpleasant; there seemed no point to me in beautifying them, or making them less direct in the fashionable manner. They came just as they are here.

WHITING

Offer it up plank it down

Golgotha was only the potegg

cancer angina it is all one to us

cough up your T. B. don’t be stingy

no trifle is too trifling not even a thrombus

anything venereal is especially welcome

that old toga virilis in the mothballs

don’t be sentimental you won’t be wanting it again

send it along we’ll put it in the pot with the rest

with your love requited & unrequited

the things taken too late the things taken too soon

the spirit aching bullock’s scrotum

you won’t cure it if you can’t endure it

it is you it equals you any fool has to pity you

so parcel up the whole issue & send it along

the whole misery diagnosed undiagnosed misdiagnosed

get your friends to do the same we’ll make use of it

we’ll make sense of it we’ll put it in the pot with the rest

it all boils down to blood of lamb*

[…]

Love ever Write often

dein Sam

Translation Notes: Liebespaar (lovers). libesfähiger (wenn es darauf [an]kommt!) — more capable of loving when it matters, “körperlich nicht ganz auf der Höhe” (physically not up to it), ”De quoi ecrire” (the wherewithal to write), Dein (your)

From The Letters of Samuel Beckett: Volume I, 1929-1940. Edited by Martha Dow Fehsenfield and Lois More Overbeck. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

FURTHER READING

Read Samuel Beckett’s play, “Endgame”, inspired by Cissie Sinclair.

Read an article about the purchase of Samuel Beckett’s first manuscript that went on display for only one day in June 2014.

Read Samuel Beckett’s play, “Breath”, the shortest play on record.