Here, Jean Rhys writes to friend Peggy Kirkaldy about the growing legal troubles of her third husband, Max Hamer. Hamer would soon be convicted of fraud and sent to prison.

Monday [1950]

Stanhope Gardens

Peggy my dear,

Max’s case comes on tomorrow, he’s with his lawyer now, and as I’m too weary to tramp about the stony streets I’ll talk to you instead and risk boring you. My dear if I’m confusing about what has happened—well I’m pretty confused too. But I’ll tell you all I know and make it as short as possible—thank you for listening.

To start at the start as Ford would say—You remember don’t you that when you came to see me at Beckenham I was full of plans for fixing up the poor old house. That was the start (at any rate so far as I know). A very plausible man who called himself a “builder” had agreed to repair the water pipes, make the basement habitable and all the rest. I was very enthusiastic about this, I was simply delighted when I thought of settling in that house and just flopping for the rest of my life. I’m awfully tired, tired to my soul, and I am not brave at all now but an almighty coward. I hadn’t the slightest reason to distrust Max. He was Leslie’s cousin, he knew I had no money when he asked me to marry him, none better, for he was the trustee (Leslie’s will). He’d been very kind to me. Also I am perfectly certain even now that Max is not a bad hat. He’s potty. I look potty, he is potty. There’s no other explanation. Listen. This builder (so called) got a hundred quid from me and three hundred from Max (to start off with). He sent some workmen along and they made a hell of a row for a week.

The second week they sat around and smoked, the third week they vanished. So did the builder, Wilson. So did the -400. Well, I was a bit shaken but not suspicious. Max repaid me my 100. When I asked why he didn’t go to the police he said it would be useless as the whole affair was black market. All accident, you see, that might happen to anyone!!

However Wilson was followed by “Wells”. His stunt was something to do with night clubs. He got 300 from Max. Then I began to get jittery—especially when Wells rang up and told me that Max was getting in with the worst gang of crooks in London.

I didn’t know what to do. Wells told me that Max was always drunk, that his new partner Yale was just out of jail and was always drunk aussi. (That was true for Yale was generally so tight by lunch time that I couldn’t understand him when he telephoned.) (When I met Max he was a partner in a firm of Lincolns Inn solicitors but they quarreled. That I think was the real start but I don’t know the details or indeed anything about the affair). Wells shortly after this useful information vanished too. So did the 300. Then Max’s association with Yale came to an end and they had an awful row.

Then my dear I went all of a doodah and of course I started to drink again—

You see I am weak and a coward and it wasn’t a pleasant situation. The house was a bit ghostly and lonely oh Lord! and my small money was melting away, gas, electricity, phone, hairdos and housecoats to woo back the straying Max. God what a fool I am! Clinging vines aren’t in it.

But remember that I was also deadly deadly tired—cannot explain how tired.

When Wells departed Roberts appeared. He was the worst. He didn’t borrow a wallop and go. He borrowed small sums but constantly—and he stayed. I mean he hung round.

About Christmas I’d worked myself into frenzy. I told Max that our marriage was a failure, and that I wanted to give it up. I asked him to repay me about 50 and let me depart. He said he was broke: I said What about Roberts? He said Roberts was a great inventor and would make his and our fortune. I swore. Then we started to quarrel—constantly. Everyone blamed me—ça va sans dire—I was a harridan, a drunkard, Heaven knows what. And bats of course.

The more they abused me, the more bitter I became, and the worse I handled the whole affair—in fact I couldn’t have behaved worse of with less tact.

I don’t know if I’ve given you the feeling that Max is a pansy. Au contraire. He is a very male creature and in a heart-rending way he is naïve. He hates my writing for instance, I’m sure of that. Perhaps I might have managed him—perhaps.

No he’s no pansy, but a gambler and as he’s grown older he’s become a crazy gambler. He clutched at any chance of making money. He talked of money constantly. That bored me to tears and I said so. Then we’d fight.

Of course there were long weeks of peace. Max got a job with Cohen & Cohen—and sometimes I pretended I was happy. Well Happy! What a word! Time marched on anyway. I didn’t drink so much but I didn’t eat much either and was desperate inside. One day the man in the flat upstairs was rude to me. I slapped his face. He had me up for assault. I had no witnesses. He had his wife and umpteen others. I began to cry in the witness box and the magistrate sent me to Holloway to find out if I was crazy. I told you about that—the Holloway people said I wasn’t crazy and sent me back to the magistrate who told me not to be violent any more plus fines of course. After that I sank into apathy as they say.

It was then or not so long afterwards that the BBC girl Selma advertised for me. I saw her and liked her. It meant a lot to me and I began to wake up and make plans and come alive again.

I wanted to do a thing about Holloway to be called Black Castle—

And it was exactly at this time that this archfiend came into the picture. This Donne or Dunn person.

I saw at once that he was up a different street—unlike the others. Very intelligent, very sensitive, and a bit mad. It also stuck out five miles that he was a crook. Max asked me what I thought of him. I was very cautious because I know Max’s mulish obstinacy, so I only said that I liked him but would he be wary about money. Max said “Oh I’m going to get him a job at Cohen’s”. Well I was fairly easy in my mind—I thought they’ll see what I saw. Here my dear is the incredible part. They didn’t.

M. Cohen père is over seventy and has been a solicitor for fifty years or something. He lives at Grosvenor House so hasn’t done badly. Cohen fils hangs about night clubs and chases theatrical ladies. You’d think wouldn’t you that those two would be cautious—not a bit of it. Inside of a week, Donne, was installed at Cohen’s office—chief cook and bottle washer. I didn’t know one instant’s peace afterwards. Every night Max would send me a wire “Detained”—I thought “Donne has produced some ghastly smart girl”. Perhaps he did— but surely if he had Max would have cut his hair and bought shirts and socks and things. Vain and obstinate as he is, surely he’d have run to a new tie!

But no. Every day he’d say “Tonight Donne’s getting me two hundred or five hundred” or a thousand and always he’d get more haggard and shabby and disappointed. I couldn’t bear it any longer, and asked him if he’d lend me enough money to go away for a week. I meant to pull myself together and do something. Well the Saturday I was to go he disappeared for five days. That was when I cracked up—physically I mean I do not think I’ll ever be well again—not really. On Thursday I determined to sell my furniture for what it would fetch and depart. On Thursday night Max turned up again dramatically. He climbed through the window and said “C’est moi”. I could only say “Tiens!” It was like a farce or a dream or both. I asked him why they’d gone to Paris. He said to borrow money because He had friends there. Apparently the celebrated charm didn’t work because they’d come back empty handed. Max told me that they’d left Cohen’s and were starting on their own in Bell Yard. He said they’d make all the money in the world because Donne knew all the crooks in London. (That part I believed). I went to their office once, it was packed with counsel clients and all the set up. Everybody hung on Donne’s Come in Go out. Aitch (that’s what he calls Max —H. fetch me this).

The clerk a nice young man told me “Mr Donne is a wonderful man. I’m proud to be working for him I’d do anything for him I’ve never met anyone like him.” I could only stare.

Well what could I think or do or say against all this? I don’t know how long it was before Max vanished again and after a few days I heard through the Law Society that Max and Donne had been arrested.

Then it all came out. Thousands were missing. Cohen, money-lenders and some clients’.

Max swears Donne had it all, I don’t know what Donne says but can guess. Still they meet, still he can hypnotise Max or so it seems.

I thought when I began all this that I’d clarify the situation but I’ve only made it more confused. I don’t know any more. I can see that Donne is clever as hell, sensitive, heartless. But all that clever? No, I don’t see it. You’ll say How could I stick? Why didn’t I do? I really had so little money and I got so weary. You don’t know. I got so that I slept all the time and the only thing I wanted was sweets. Yes my dear sweets.

I cannot explain how this anxiety can smash one up.

Well you’ll say Max is a rogue. No he isn’t. He’s mad for money and Donne hypnotized him. He says he wanted it for me. That isn’t all true but it may be a bit true. He just wanted it. He may have spent some on women or a woman but not much. He doesn’t give me that feeling—besides he is too cynical. I simply can see nothing clearly at all. It’s crazy. I can’t think how Donne got rid of it all or why they keep on seeing each other.

My dear have you read all this? I may as well bring it up to date. Yesterday I had a letter from a solicitor in Lincolns Inn Fields. A friend who wishes to remain anonymous will supply me with money to live on for the present. I don’t know who it is. Certainly not my relative. Max says Lord Listowel who’s a friend or relative of something—or a combination of his sister and Listowel I don’t know and hardly care. It’s all very uncertain—I don’t know whether to stay in London and see people or go away and rest.

I must rest a bit, I must or I’ll crash utterly. But I must be careful where I go for they’ll only pay my hotel bill and there’s not any margin for mistakes. I want somewhere to rest where they’ll just let me rest.

Perhaps I’ll find something in the New Statesman. I thought of your place in Monmouth, but it’s a long way off.

I don’t know Eric Ambler’s books and I’d like to meet him and his wife. But I must be better first. I cry so easily and fly into a rage so easily that I’m not fit for human society.

I haven’t written to anybody tho’ Selma heard the dire news and wrote me a very nice letter. She’s a good sort. I must write and try to see her.

Peggy I’d like a job in a shop but alas I am not chic or elegant. I’m grotesque except somebody else dresses me and advises me. I was all right sometimes in Paris because Jean bought all my clothes. Funny—he was odd about money too.

And Peggy to show how hopeless I am, I cannot type. Can you beat it? You see I didn’t revise so much my first two books. Then Leslie used to say he liked typing tho’ I bet he didn’t really.

I’m lazy and hopeless Peggy but honestly I do have a rum time.

Love

Jean

Max has just come in. his thing had been adjourned. Donne’s mother wants to meet us. Well with what human curiosity I’ve left I like to hear about Mr Donne’s mother.

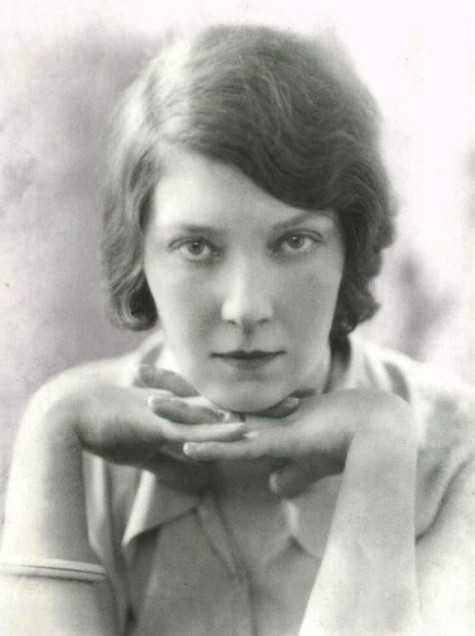

From The Letters of Jean Rhys. Rhys, Jean, Diana Melly, and Francis Wyndham. New York, NY: Viking, 1984.