Oscar Wilde writes to W.E. Henley, the editor of the conservative journal The Scots Observer, concerning their review of The Picture of Dorian Gray. The journal suggested that the novel was “false art” because it misrepresented human nature and morality. The controversial exchange began on July 9, 1890, when Wilde sought to address The Scots Observer’s remark that he had a habit of “writing stuff that were better unwritten.” Below, Wilde writes the journal for the third and last time. Prior to this dispute, Wilde had also responded to criticism from The Daily Chronicle and exchanged multiple letters with the St. James’s Gazette, which insisted upon its right to express its opinion about Wilde’s “dull and nasty” novel.

13 August 1890

Sir, I am afraid I cannot enter into any newspaper discussion on the subject of art with Mr Whibley, partly because the writing of letters is always a trouble to me, and partly because I regret to say that I do not know what qualifications Mr Whibley possesses for the discussion of so important a topic. I merely noticed his letter because, I am sure without in any way intending it, he made a suggestion about myself personally that was quite inaccurate. His suggestion was that it must have been painful to me to find that a certain section of the public, as represented by himself and the critics of some religious publications, had insisted on finding what he calls “lots of morality” in my story of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Being naturally desirous of setting your readers right on a question of such vital interest to the historian, I took the opportunity of pointing out in your columns that I regarded all such criticisms as a very gratifying tribute to the ethical beauty of the story, and I added that I was quite ready to recognize that it was not really fair to ask of any ordinary critic that he should be able to appreciate a work of art from every point of view. I still hold this opinion. If a man sees the artistic beauty of a thing, he will probably care very little for its ethical import. If his temperament is more susceptible to ethical than to aesthetic influences, he will be blind to questions of style, treatment, and the like. It takes a Goethe to see a work of art fully, completely, and perfectly, and I thoroughly agree with Mr Whibley when he says that it is a pity that Goethe never had an opportunity of reading Dorian Gray. I feel quite certain that he would have been delighted by it, and I only hope that some ghostly publisher is even now distributing shadowy copies in the Elysian fields, and that the cover of Gautier’s copy is powdered with gilt asphodels.

You may ask me, sir, why I should care to have the ethical beauty of my story recognized. I answer, simply because it exists, because the thing is there. The chief merit of Madame Bovary is not the moral lesson that can be found in it, any more than the chief merit of Salammbô is its archaeology; but Flaubert was perfectly right in exposing the ignorance of those who called the one immoral and the other inaccurate; and not merely was he right in the ordinary sense of the word, but he was artistically right, which is everything. The critic has to educate the public; the artist has to educate the critic.

Allow me to make one more correction, sir, and I will have done with Mr Whibley. He ends his letter with the statement that I have been indefatigable in my public appreciation of my own word. I have no doubt that in saying this he means to pay me a compliment, but he really overstates my capacity, as well as my inclination for work. I must frankly confess that, by nature and by choice, I am extremely indolent. Cultivated idleness seems to me to be the proper occupation for man. I dislike newspaper controversies of any kind, and of the two hundred and sixteen criticisms of Dorian Gray that have passed from my library table into the waste-paper basket I have taken public notice of only three. One was that which appeared in the Scots Observer. I noticed it because it made a suggestion about the intention of the author in writing the book, which needed correction. The second was an article in the St James’s Gazette. It was offensively and vulgarly written, and seemed to me to require immediate and caustic censure. The tone of the article was an impertinence to any man of letters. The third was a meek attack in a paper called the Daily Chronicle. I think my writing to the Daily Chronicle was an act of pure willfulness. In fact, I feel sure it was. I quite forget what they said. I believe they said that Dorian Gray was poisonous, and I thought that, on alliterative grounds, it would be kind to remind them that, however that may be, it is at any rate perfect. That was all. Of the other two hundred and thirteen criticisms I have taken no notice. Indeed, I have not read more than half of them. It is a sad thing, but one wearies even of praise.

As regards Mr Brown’s letter, it is interesting only in so far as it exemplifies the truth of what I have said above on the question of the two obvious schools of critics. Mr Brown says frankly that he considers morality to be the “strong point” of my story. Mr Brown means well, and has got hold of a half-truth, but when he proceeds to deal with the book from the artistic standpoint he, of course, goes sadly astray. To class Dorian Gray with M. Zola’s La Terre is as silly as if one were to class Masset’s Fortunio with one of the Adelphi melodramas. Mr bown should be content with ethical appreciation. There he is impregnable.

Mr Cobban opens badly by describing my letter, setting Mr Whibley right on a matter of fact as an “impudent paradox.” The term “impudent” is meaningless, and the word “paradox” is misplaced. I am afraid that writing to newspapers has a deteriorating influence on style. People get violent, and abusive, and lose all sense of proportion, when they enter that curious journalistic arena in which the race is always to the noisiest. “Impudent paradox” is neither violent nor abusive, but it is not an expression that should have been used about my letter. However, Mr Cobban makes full atonement afterwards for what was, no doubt, a mere error of manner, by adopting the impudent paradox in question as his own, and pointing out that, as I had previously said, the artist will always look at the work of art from the standpoint of beauty of style and beauty of treatment, and that those who have not got sense of beauty, or whose sense of beauty is dominated by ethical considerations, will always turn their attention to the subject-matter and make its moral import the test and touchstone of the poem, or novel, or picture, that is presented to them, while the newspaper critic will sometimes take one side and sometimes the other, according as he is cultured or uncultured. In fact, Mr Cobban converts the impudent paradox into a tedious truism, and, I dare say, in doing so does good service. The English public like tediousness, and like things to be explained to them in a tedious way, Mr Cobban has, I have no doubt, already repented of the unfortunate expression with which he has made his début, so I will say no more about it. As far as I am concerned he is quite forgiven.

And finally, sir, in taking leave of the Scots Observer I feel bounded to make a candid confession to you. It has been suggested to me by a great friend of mine, who is a charming and distinguished man of letters, and not unknown to you personally, that there have been really only two people engaged in this terrible controversy, and that those two people are the editor of the Scots Observer and the author of Dorian Gray. At dinner this evening, over some excellent Chianti, my friend insisted that under assumed and mysterious names you had simply given dramatic expression to the views of some of the semi-educated classes in our community, and that the letters signed “H” were your own skillful, if somewhat bitter, caricature of the Philistine as drawn by himself. I admit that something of the kind had occurred to me when I read “H’s” first letter—the one in which he proposed that the test of art should be the political opinions of the artist, and that if one differed from the artist on the question of the best way misgoverning Ireland, one should always abuse his work. Still, there are such infinite varieties of Philistines, and North Britain is so renowned for seriousness, that I dismissed the idea as one unworthy of the editor of a Scotch paper. I now fear that I was wrong, and that you have been amusing yourself all the time by inventing little puppets and teaching them how to use big words. Well, sir, if it be so—and my friend is strong upon the point—allow me to congratulate you most sincerely on the cleverness with which you have reproduced the lack of literary style which is, I am told, essential for any dramatic and life-like characterization. I confess that I was completely taken in; but I bear no malice; and as you have no doubt been laughing at me in your sleeve, let me now join openly in the laugh, though it be a little against myself. A comedy ends when the secret is out. Drop your curtain, and put your dolls to bed. I love Don Quixote, but I do not wish to fight any longer with marionetters, however cunning may the master-hand that works their wires. Let them go, sir, on the shelf. The shelf is the proper place for them. On some future occasion you can re-label them and bring them out for out amusement. They are an excellent company, and go well through their tricks, and if they are a little unreal, I am not the one to object to unreality in art. The jest was really a good one. The only thing that I cannot understand is why you gave your marionettes such extraordinary and improbable names. I remain, sir, your obedient servant

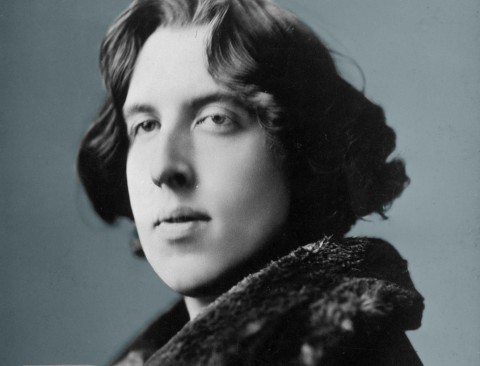

OSCAR WILDE