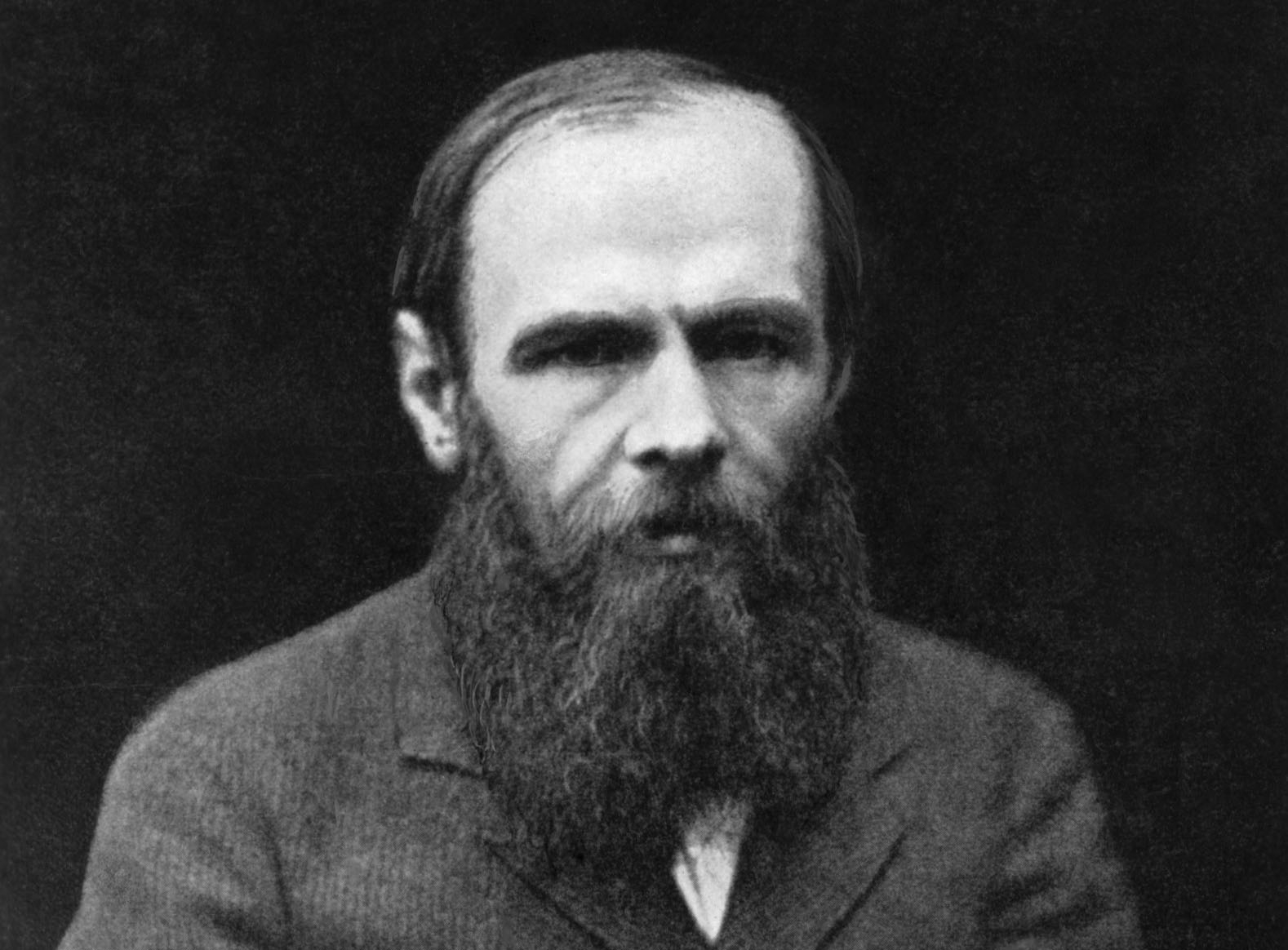

Below, a broke, struggling Dostoyevsky pitches Crime and Punishment to the editor of a literary magazine. (NB: Today, we’re cheating a bit. The letter is dated, on the basis of available evidence, not to “12 September”, but rather to “first half of September 1865”. And, as the window for “first half of September” has nearly closed, we thought we’d slip this in today.)

TO M.N. Katkov

[First half of September], 1865, Wiesbaden

K[ind] S[ir] M[ikhail] N[ikiforovich]

May I hope to have my story published in your magazine, R[ussian] M[essenger]?

I have been working on it for 2 months now here in Wiesbaden, and it is nearing completion. It will contain between five and six printer’s sheets. I still have a couple of weeks’ work left on it, or perhaps a bit more. In any case, I can promise definitely that in a month at the very latest I could deliver it to the editorial offices of R.M.

The idea of my story, as far as I can see, in no wise runs counter to your magazine. Indeed, quite the contrary. It is a psychological account of a crime. The action is topical, set in the current year. A young student of lower-middle-class origin, who has been expelled from the university, and who lives in dire poverty, succumbs—through thoughtlessness and lack of strong convictions—to certain strange, “incomplete” ideas that are floating in the air, and decides to get out of his misery once and for all. He resolves to kill an old woman, the window of a titular councilor, who lends out money for interest. The old crone is stupid, deaf, sick, and greedy[…] She is wicked and makes the life of her younger sister, whom she treats as a servant, wretched. “She is good for nothing,” “what does she live for?” “Is she of any use to anyone at all?” and so on. These questions disorient the young man. He decides to kill and rob her in order to bring happiness to his mother, who is living in the provinces, and to wrest his sister, who is living as a companion in the house of some landowners, from the lewd demands of the head of the household, demands that may lead to her perdition. He also wants to finish his studies and to go abroad and, afterward, for the rest of his life, to be honest, firm, and steadfast in the performance of his “humanitarian duties toward mankind,” which certainly would “expiate his crime,” if one can actually call a crime his act against a stupid, deaf, vicious, sick old crone who herself does not know why she is living and who may die anyway in a month or so.

Despite the fact that such crimes are very difficult to carry out, i.e., criminals practically always leave glaring clues, evidence, etc., behind them, and leave too much to chance, which almost always leads to their discovery, he, by sheer accident, carries off the execution of his enterprise quickly and successfully.

Afterward, almost a month goes by before the final catastrophe. He is not and cannot possibly be suspect. And it is just at this point that the entire psychological process of crime unfolds itself. Insoluble problems arise before the murderer; unsuspected and unforeseen feelings torment his mind. Divine truth and human law take their toll, and he ends up by being driven to give himself up. He is driven to this because, even though doomed to perish in penal servitude, it will make him on with the people again, and the feeling of being cut off and isolated from humanity that he had experienced from the moment he committed the crime had been torturing him. The law of truth and human nature won out […] The criminal himself decides to accept suffering to expiate his deed. However, it is rather difficult for me to make my idea completely clear.

Besides this, my story contains the suggestion that the legal penalty imposed for the commission of a crime frightens the offender less than the lawmakers think, partly because it is he himself who demands it morally.

I have seen that myself in even the most backward individuals in the crudest circumstances. I would like to show that this feeling is present in an educated man of the new generation, so that the idea would be more striking and more tangible. Several recent occurrences have convinced me that there is nothing terribly unusual about my subject, namely, the fact that my murderer is well educated and is even a young man with praiseworthy inclinations. Last year in Moscow I heard of a student who, expelled from the university after the Moscow student disorders, decided to break into a post office and kill a postal employee. There is also considerable evidence in our newspapers that the extreme inconstancy of our principles has resulted in horrible acts. (The seminary student who made a pact with a young girl to kill her, killed her in a barn, and was picked up one hour later while he was eating his lunch, and other such things.) In brief, I am convinced that my subject will in a way explain what is happening today.

It goes without saying that this outline of the idea of my story entirely leaves out the plot. But it will be engrossing—that I will vouch for—although I cannot take it upon myself to judge its artistic merits. I have been too often forced to write very, very poor pieces because I have had to hurry to meet deadlines, etc. But this particular story has been written unhurriedly and with ardor. And I shall try, if only for my own sake, to make the ending as good as I can. […]

I leave the price entirely to your discretion—you may determine it after you have read my story. I understand that many writers working with you proceed in this way. But in any case, I should like to get per printer’s sheets no less than the minimum I have been receiving up to now, i.e., 125 rubles. But again, I leave this entirely up to you, and I firmly believe that that will be to my best advantage.

Forgive me if I pass on now to my private affairs. I find myself in a very bad situation at the moment. I went abroad at the beginning of July with hardly any money, to gain back my health. I was hoping to wind up a work I had started, but then I got involved in another story (the one I am writing now) and I do not regret it. However, this forces me to ask you for an advance of three hundred rubles now, in the event, of course, that you are interested in my work. I beg you, much esteemed Mikhail Nikifor., not to view my request for 300 rubles as in any way a condition for offering my piece to you. That is not the case at all. It is simply a favor I am asking of you to help me out at a particularly difficult moment and, of course, a favor which is worthy of consideration only if—I repeat again—you manifest your willingness to take my work. […]

Whatever your decision, I should greatly appreciate it if you did not leave me for a long time without an answer from the editors of your magazine. In my present straits, every minute is precious. I imagine that, although I myself hope to be back in Russia in a month, I shall be able to send you my work in three weeks.

All Yours,

F. Dostoyevsky

+

FURTHER READING

A paucity of sources here (at least, sources kicking around for free on the internets), which is surprising. Suffice it to say that Dostoyevsky was deep in debt, and his reaching out to M.N. Katkov—about whom, over the course of the preceding years, he had penned a number of slanderous, incendiary polemics—was something of a last resort. Katkov, however, responded with great kindness, forwarding Dostoyevsky both the initial advance of 300 rubles and, some months later, an additional advance of 700. Beyond that—if you find something good for today’s letter, let us know: editors@theamericanreader.com.