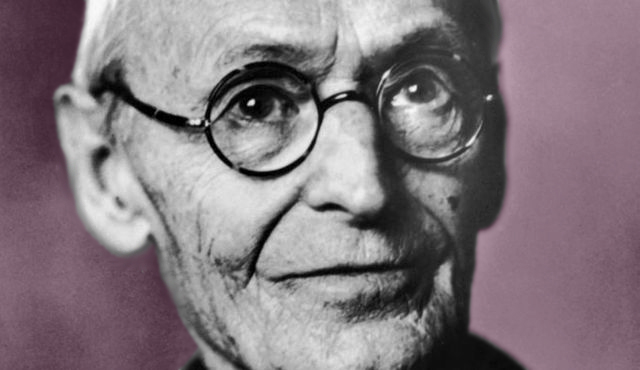

In this letter from 1939, Hermann Hesse writes to his friend Max Herrmann-Neisse, expressing his concern for friends living in Poland and Prague, and explaining his personal detachment from world events, afforded to him by his old age.

To Max Herrmann-Neisse

December 1939

Your letter with the very welcome poems arrived recently, with only a slight delay. I would like to thank you; I enjoyed reading something of yours again and discovering how you’re faring.[1]

The last few months have been quite hectic and unsettling, because we were getting some quite necessary construction done, which took a lot out of my wife, but it’s almost finished now. The war has, of course, left its mark on us too, in several ways. My wife had close relatives and some old friends living in Poland and hasn’t heard yet whether any of them have survived; we are particularly worried about friends of hers in Prague who haven’t managed to get out yet. And my three sons are in the Swiss Army and have been on active duty since the outbreak of war. I’m not all that interested in world events. Old people don’t care very much anymore how the elements no longer capable of life get eliminated, even if that process is quite diabolical. I firmly believe that man is endowed with a certain sense of stability, and it seems to me that he awakes from every abomination with a bad conscience, and so each corrupt period gives rise to a new yearning for meaning and order—but I do not believe that I shall live to experience the next upward motion after this present downward slide. I’m old and tired.

Our region is very quiet and there is very little sign of the war, as opposed to the situation in German Switzerland. And finally, at the very end of a rainy year, we are having a spell of beautiful, steady weather and days of gentle sunshine. Pictorially, the colors in our landscape are most beautiful in winter, especially before the first snow has fallen. Everything is suffused in a soft, intense glow, and then at twilight, when the mountains seem to light up from within, the spectacle culminates in an intimate festival of light, which always seems like a silent, smiling protest of the friendly, enduring, motherly powers against the antics of world history.

[1] Since September 1933, the writer Max Herrmann-Neisse had been living with his wife in voluntary exile in London.