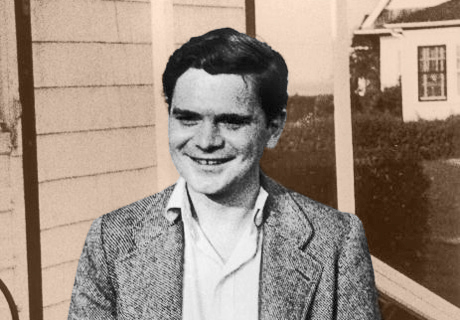

When painter Fairfield Porter first met James Schuyler, he promptly developed a crush on the young poet. Porter made a strong impression on Schuyler as well: the poet not only dedicated his first collection, Freely Espousing, to Porter and his wife, poet Anne Porter, but also wove the painter into his own verse. Porter, who produced several portraits of Schuyler, would eventually invite him to move in with the Porter family in Southampton, where Schulyer would remain for well over a decade. Below, some six years before their uneasy cohabitation, Schuyler writes to Porter about, among other things, the age gap in their relationship and the value of “oddness” in a person.

New York, New York

Late Fall, 1955

Dear Fairfield,

How delightful to find your handwriting in an anonymously addressed envelope, when I dismally thought all the mail was another throw-away. I shall go right away to see Calcagno, and Feeley too.

But how inaccurate of you to have told Frank and Kenneth that the reason you didn’t call me is that it is you who always call! Wasn’t it I who called you in Southhampton when I heard you were back and coming into town? And I who called you the day we were moving, when you and I went downtown and you bought the beautiful white lamp that has given us so much pleasure and illumination? And often when it has been you who called, wasn’t it because we had arranged it so beforehand—as often my suggestion as yours—on the grounds that you would be out during the day, and I would be in? I did try to call you the week of John’s party, and then gave it up because I was aware of a deliberateness in your silence. One’s often tempted to test one’s friends in these little ways—at least I am—but it’s my experience that to do so is a challenge to the friend to show that he has the nerve and heartlessness to fail one; and most of us have. Besides, I think you exaggerate the degree of initiative you take in your friendships: I know, because I’m shy, that it often takes more initiative for me to bring myself to say yes to an invitation than it took for the inviter to issue it.

While I’m at it, I’m also rather put out by this youth and age stuff. In so far as I think of you as “older,” I feel honored and benefited by your friendship; but if it turns out that you feel odd in bestowing it, I feel snubbed. I don’t, though, think of you as “older” so much as I do a friend who has had a life very different from mine (but if I must think about it, then I say that I think I’m a man over thirty, past which age one might hope to have gained the right to mingle with one’s elders &/or betters). I wish I thought you dwelt a little on the virtues of your behavior: and saw that if (as I hope you do) you take pleasure in the company of Frank and Jane and Kenneth and Barbara and the rest of us, it’s because your mind hasn’t sealed over, that you’ve kept a fresh enthusiasm and curiosity, a desire to catch the contagion from your creative people and at the same time to help and instruct: equally admirable. How grateful John Button is to you for the things you said to him about his painting, and who else is there who could say them? Someone else might OK his pictures— but that’s just approval; someone his own age might criticize them in a helpful way, but that would lack the validity of experience. I cannot, literally bring to mind anyone else who would and could do it: Tom Hess wouldn’t; Alfred Barr is too diplomatic; Larry would be jealous; John Myers is a dope…and so on. (I thought his paintings beautiful, and praised them as best I could; but I certainly have no painting pointers to give him!) All I mean is that it seems to me merely another instance of American self-consciousness when confronted by one’s oddness, when the oddness is what makes value. Do you think your paintings could keep gaining in quality—as I think they do—if you had been one of those dreary artists who hunt for it in their twenties, find it in their thirties and then do it for the rest of their lives? Oh the acres of Kuniyoshi and Reginald Marsh: I don’t say their work is without merit, but I think it’s mostly an achieved manner, and manner, en masse, makes for ennui. I wish instead of odd, you thought yourself as unique; you seem so to me, in relation to your brothers and sisters, to other artists, to other men your age, to other members of the class of ’28 (if that is the right year)—but then, they haven’t had a long draught from the only spring that matters. You have.

I hope this doesn’t seem impudent and fresh; which was no part of my plan. Frank is not going to review anymore, and Betty Chamberlin called and asked if I’d write three sample reviews; so I shall, over the weekend. I wish you were going to be here to criticize them for me, but I shall do the best that I can and keep copies to show you.

I hope soon I can come out and visit you; since you said at Morris’s I knew “damn well I could.” Pretty strong talk, pardner.

I’m enjoying enormously working over my book with Catherine Carver; I think it will turn out one that I will like much more than the one I submitted. It seems as though every place where she puts her finger is one I had at some time thought myself might be a little pulpy or squashy.

I’ll write more chattily another time, when you tell me that you’ve forgiven me for anything in this letter that needs forgiving. None of it means anything serious, in the light of the joy it gave me to see your face light up when you finally saw me signaling wildly from that moving cab.

My love to Anne and Kitty and yourself. I long to hear news of Jerry.

as always, Jimmy

PS Would you call me next Tuesday? I expect to be in all day.

From Just the Thing: Selected Letters of James Schuyler, 1951-1991. Edited by William Corbett. New York: Turtle Point, 2004. Print.

FURTHER READING

Read a selection from Schuyler’s vivid oeuvre, A Man in Blue.

Examine the works of Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Reginald Marsh, which Schuyler found “mannered” compared to Porter’s.

Read an interview with Schuyler, conducted a year before he passed away.