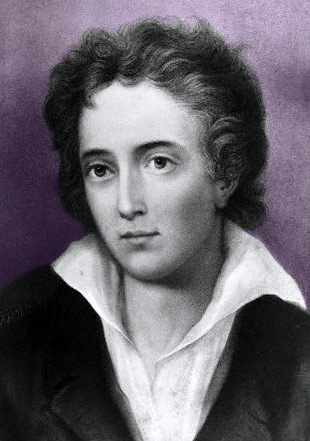

Miss Hitchener and Percy Bysshe Shelley met shortly before this letter was written. She was the schoolmistress of a daughter of Shelley’s uncle. Struck by Hitchener’s liberal views, Shelley wrote to her frequently during summer of 1811 on the subjects of philanthropy and religious philosophy. After a few months of this, Shelley, realizing that his letters might have made the wrong impression, felt compelled to tell Hitchener of his impending marriage to Harriet Westbrook. Many were aware of Hitchener’s correspondence with Shelley, suspecting that she was his mistress, though there is no proof of that being the case. Later on, Miss Hitchener closed her school in order to join the Shelley family only to be shunned; Shelley’s initial interest in her had waned.

11 June 1811

My Dear Madam,

With pleasure I engage in a correspondence which carries its own recommendation both with my feelings and my reason… I am now, however, an undivided votary of the latter. I do not know which were most complimentary: but as you do not admire, as I do not study, this aristocratical science, it is of little consequence.

Am I to expect an enemy or an ally in Locke? Locke proves that there are no innate ideas, that in consequence, there can be no innate speculative or practical principles, thus overturning all appeals of feeling in favor of Deity, since that feeling must be referable to some origin. There must have been a time when it did not exist; in consequence, a time when it began to exist. Since all ideas are derived from the senses, this feeling must have originated from some sensual excitation, consequently the possessor of it may be aware of the time, of the circumstances, attending its commencement…Locke proves this by induction too clear to admit of rational objection. He affirms, in a chapter of whose reasoning I leave your reason to judge, that there is a God; he affirms also, and that in a most unsupported way, that the Holy Ghost dictated St. Paul’s writings. Which are we to prefer? The proof or the affirmation?

…To a belief in Deity I have no objection on the score of feeling: I would as gladly, perhaps with greater pleasure, admit than doubt his existence…I now do neither, I have not the shadow of a doubt…

My wish to convince you of his non-existence is twofold: first on the score of truth, secondly because I conceive it to be the most summary way of eradicating Christianity…I plainly tell you my intentions and my views… I see a being whose aim, like mine, is virtue….Christianity militates with a high pursuit of it… Hers is a high pursuit of it…she is therefore not a Christian. Yet wherefore does she deceive herself? Wherefore does she attribute to a spurious, irrational (as proved), disjointed system of desultory ethics, insulting, intolerant theology—that high sense of calm dispassionate virtue which her own meditations have elicited? Wherefore is a man who has profited by this error to say: “you are regarded as a monster in society; eternal punishment awaits your infidelity?” “I do not believe it,” is your reply. “Here is a book,” is the rejoinder. “Pray to the being who is here described, and you shall soon believe.”

Surely, if a person obstinately wills to believe,—determines in spite of himself, in spite of the refusal of that part of mind to admit the assent, in which only can assent rationally be centered, wills thus to put himself under the influence of passion, all reasoning is superfluous…Yet I do not suppose that you act thus (for action it must be called, as belief is a passion); since the religion does not hold out high morality as an apology for an aberration from reason…In this latter case, reason might sanction the aberration, and fancy become but an auxiliary to its influence.

Dismiss then Christianity, in which no arguments can enter…passion and reason are in their natures opposite. Christianity is the former and Deism (for we are now no further) is the latter…

What then is a “God”? It is a name which expresses the unknown cause, the suppositious origin of all existence. When we speak of the soul of man, we mean that unknown cause which produces the observable effect evinced by his intelligence and bodily animation, which are in their nature conjoined, and (as we suppose, as we observe) inseparable. The word God then, in the sense which you take it analogises with the universe, as the soul of man to his body, as the vegetative power to vegetables, the stony power to tones. Yet, were each of these adjuncts taken away, what would be the remainder? What is man without his soul? he is not man…What are vegetables without their vegetative power? stones without their stony? Each of these as much constitutes the essence of men, stones, etc., as much make it to be what it is, as your “God” does the universe. In this sense I acknowledge a God, but merely as a synonime [sic] for the existing power of existence….

I do not in this (nor can you do, I think) recognize a being which has created that to which it is confessedly annexed as an essence, as that without which the universe would not be what it is. It is therefore the essence of the universe, the universe is the essence of it. It is another word for the essence of the universe. You recognize not in this an identical being to whom are attributable the properties of virtue, mercy, loveliness—imagination delights in personification; were it not for this embodying quality of eccentric fancy we should be to this day without a God…Mars was personified as the god of war, Juno of policy, etc.

But you have formed in your mind the Deity of virtue; this personification beautiful in Poetry, inadmissible in reasoning, in the true style of Hindoostanish devotion, you have adopted…I war against it for the sake of truth….There is such a thing as virtue, but what, who, is this Deity of virtue? …Not the Father of Christ, not the source of the Holy Ghost; not the God who beheld with favor the coward wretch Abraham, who built the grandeur of his favourite Jews on the bleeding bodies of myriads, on the subjugated necks of the dispossessed inhabitants of Canaan. But here my instances were as long as the memoir of his furious King-like exploits, did not contempt succeed to hatred. Did I now see him seated in gorgeous and tyrannic majesty, as described, upon the throne of infinitude…if I bowed before him, what would virtue say? Virtue’s voice is almost inaudible, yet it strikes upon the brain, upon the heart…The howl of self-interest is loud…but the heart is black which throbs solely to its note…

You say our theory is the same: I believe it. Then why all this? The power which ma[kes] me a scribbler knows!

I have just finished a novel of the day—”The Missionary,” by Miss Owenson. It dwells on ideas which when young I dwelt on with enthusiasm, now I laugh at the weakness which is passed…

Yet I forgot….I intended to mention to you something essential. I recommend reason.—Why? Is it because, since I have devoted myself unreservedly to its influencing, I have never felt happiness? I have rejected all fancy, all imagination; I find that all pleasure resulting to self is thereby completely annihilated. I am led into this egotism, that you may clearly be aware of the nature of reason, as it affects me. I am sincere: will you comment upon this?

Adieu. A picture of Christ hangs opposite in my room: it is well done, and has met my look at the conclusion of this. Do not believe but that I am sincere…but am I not too prolix?

Yours most sincerely,

Percy Shelley

From Letters from Percy Bysshe Shelley to Elizabeth Hitchener: Volume I. London: Privately published, 1890. pp. 6-14.

FURTHER READING

Read Shelley’s essay on the necessity of atheism, which led to his expulsion from Oxford University.

“A Poem in Blank Verse” by Elizabeth Hitchener, Weald of Sussex.