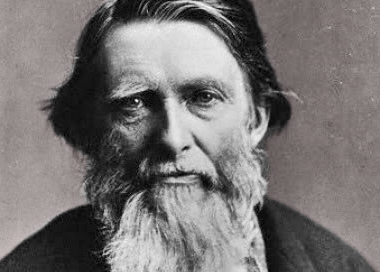

In 1858 John Ruskin started working as a drawing tutor for the La Rouche family in order to subsidize his writing. Upon first meeting the ten-year-old Rose, he was quite taken with her strong gaze and presence. While tutoring her he developed a romantic attachment and, when she turned nineteen, he proposed. Believing herself to be too young, and taking contention with his religious skepticism (a fervent Evangelical, she once asked “How could one love you if you were a pagan?”), Rose refused. The following years brought a gradual decline in her mental and physical health, and she eventually died from what is believed to be anorexia in 1876. Ruskin held her head in his arms on her deathbed. He wrote the following letter after his proposal’s rejection.

Denmark Hill

March 1868

Dear Mrs. Cowper,

Your letter comforts me, in interpreting—but does not comfort in transferring the cause of silence to this error of mine however great, or painful to her it may have been: For it was an inevitable one. I cannot ask pardon for it.

I have done Rose no wrong from the hour when she entered the room a child of ten years old, to this instant. I have loved, honored—cherished—trusted—forgiven—and all these limitlessly. For her I have borne every form of insult. For her, I have been silent in pain—for her I have labored, and wept; for her, I have died, for my heart is dead within me. And if, now, she cannot pardon—nay, if she even counts as a sin needing pardon, my belief that she dared not have cast away this so great love, unless in sure knowledge of some fatal obstacle to our marriage, such as she could only have obtained by conversation with other women, (—how else could she have known how I lived with my former wife?)—if—I say, she holds this for a sin in me—it is I whose forgiveness would be withdrawn. The very greatness of my love would make such sin against it, infinite.

If she chooses, because I thought of her as a woman, not a child;—because I thought her so pure and holy that no knowledge could stain nor dishonor touch her—because I believed her word of pledge to me inviolable, unless by mortal compelling of Fate—because I did not believe that in breaking that pledge, she could have been comforted by any friend who did not know the reason of her doing so,—but was advising her to baseness of falsehood in the name of Religion—If for these sins against her, she rejects my love—Be it so. But I do not believe it: nor will you, when you are able to measure this thing with your now perfect knowledge of it. I have never rejected her. She, without mercy—without appeal—without a moment of pause, rejected me. And now—I will take her—for Wife—for Child,—for Queen—for any Shape of fellow-spirit that her soul can wear, if she will be loyal to me with her love.

But if not—let her go away, and stain every stone of it with my blood upon her feet, forever. Mine will be shorter—The Night is Far Spent.

Ever faithfully Yours,

J Ruskin.

From The Letters of John Ruskin to Lord and Lady Mount Temple. Columbus: Ohio State University Press (1964), p. 138-139.

FURTHER READING

The effect of Rose’s death on Ruskin’s later life.

The unconsummated marriage to Effie Gray (referenced above).

The writing of Praeterita, Ruskin’s autobiography, in which he describes meeting Rose.