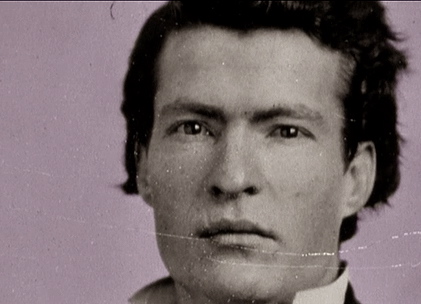

While courting his soon-to-be wife Olivia Langdon, Mark Twain found a cunning ally in Harriet Lewis, Langdon’s cousin. Twain devoted all his attention to Lewis, who pretended to be object of his interest in an act designed to protect Langdon’s privacy. Society reporters took the bait, announcing the engagement of Lewis and Twain to the nation’s newspapers. The cousins, delighted with the success of the ruse, wrote a joint letter to Twain in which Lewis expressed mock despair at discovering that she had been usurped as his prospective wife: “I [am] getting pale and emaciated, etc.”

10 January 1869

Galesburg, Illinois

Dear Miss Harriet Lewis,

(No, that is too cold for a breaking heart—)

Dear Hattie—It cannot but be painful, I may even go so far as to say harrowing, to me, to say that which I am about to say. And yet the words must be spoken. I feel that it would be criminal to remain longer silent. And yet I come to the task with deep humiliation. I would avoid it if I could. Or if you were an unprotected female. But it must out. I grieve to say there has been a mistake. I did not know my own heart. After following you like your shadow for weeks—after signing at you, driving out with you, looking unutterable things at you—after dreaming about you, night after night, & playing solitary cribbage with you day after day—after rejoicing in your coming & grieving at your going, since all sunshine seemed to go with you—after hungering for you to that degree for two days I ate nothing at all but you—after longing for you & yearning for you, & taking those twenty double-postage letters to you, lo!, at last I wake up & find it was not you after all! I never was so surprised at anything in all my life. You never will be able to believe that it is Miss Langdon instead of you—& yet upon my word & honor it is. I am not joking with you, my late idol—I am serious. These words will break your heart—I feel they will—alas! I know they will—but if they don’t damage your appetite, Mr. Langdon is the one to grieve, not you. A broken heart won’t set you back any.

Try and bear up under this calamity. O sad heart, there is a great community of generous souls in good Elmira, & you shall not sorrow all in vain. Trot out your “wasted form” & plead for sympathy. And if this fails, the dining room is left. Wend thither, weeping mourner, & augment the butcher’s bills as in the good old happy time. Bail out your tears & smile again. Don’t pass any more sleepy days & nights on my account—it isn’t complimentary to me. And you were unusually distraught & sleepy of late, I take it, for you dated your letter “December” 4 instead of January. I know what that indicates. If you will look through those twenty letters you will find that I was in a perfectly awful state of mind whenever I dated one of them as insanely as that.

It grieves me to the heart to be compelled to inflict pain, but there is no help for it, & so you will have to go to Mr. Langdon & explain to him frankly what I meant by such a conduct as those—& confess to him, for me, that it was the other young lady instead of you. And I wish you would tell her, also, for otherwise she will never suspect it, all my conversations with her having been strictly devoted to weather. Come—move along lively, now! […]

Are you well, my poor Victim? How is your haggard face? What do you take for it? Try “S.T.—1860—X.” And have you hollow eyes, too?—or is most of the holler in your mouth? I am sorry for you, my wilted geranium.

And next you’ll fade, I suppose—they all do, that get in your fix—& then you’ll pass out, along with Sweet Lily Dale, & Sweet Belle Mahone, & the rest of the tribe—& there’ll be some ghastly old sea-sickening sentimental songs ground out about you & about the place where you prefer to be planted, & all that sort of bosh. Do be sensible & don’t.

But deserted & broken-hearted mourner as you are, you are a good girl; & you are with those who love you & would make your life peaceful & happy though your heart were really torn & bleeding, & freighted with griefs that were no counterfeit. You are where you deserve to be—beyond the reach & lawful jurisdiction of wasting sadnesses & heartaches and where no trouble graver than a passing, fancied ill, is like to come to you. And there I hope to find you when I come again, you well-balanced, pleasant-spirited, excellent girl, whom I love to hold in warm & honest friendship.

Sincerely,

Saml. L. Clemens

P.S.—This is NO. 22. Don’t be foolish, now, & silent, merely because I believe the other young lady is without her peer in all the world, but write again, please. Tell me more of your wretchedness. I can make you perfectly miserable, & then you’ll feel splendid. I am equal to a good many correspondences.

Notes: The wilted geranium was found in advertisements for P.H. Drake’s Plantation Bitters, a stomach tonic.

Sweet Lily Dale and Sweet Belle Mahone were heroines featured in popular ballads from the era. Both came to the same end of death by disappointed love.

From Mark Twain’s Letters, volume 3. Edited by Edgar Marquess Branch and Michael B. Frank. Berkeley: University of Califronia Press, 1988.

FURTHER READING

A letter from later in January in which Twain gushes over a porcelain engraving sent by Olivia Langdon.

Langdon’s ink-stained fingers: her correspondences with Twain’s publishers.

Twain in the company of women.