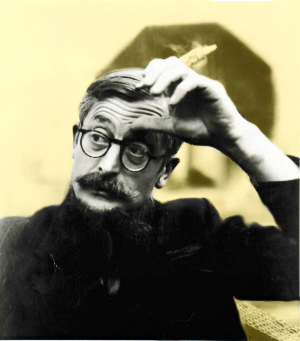

William Empson

William Empson

Below, literary critic and poet William Empson writes to the editors of the New Statesman, defending his review of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, ed. by Martin Seymour-Smith (1963), against Seymour-Smith’s own rebuttal of the review. It would seem the major point of contention pertained to sonnet 144, and whether or not the phrase “to fire out” meant (as Seymour-Smith argued) “to communicate venereal disease.” Seymour-Smith also called Empson’s readings of the sonnets “rather perverse.”

TO THE NEW STATESMAN

November 1, 1963

Sir,—

I have followed up the chain of scholarly references purporting to prove that the Dark Lady is accused of having gonorrhoea, and it is even feebler than I expected. None of the critics mentioned in the New Variorum footnotes (At the last line of Sonnet 144) says anything about this idea; the authors in periodicals for 1901 and 1907, who might seem presented as discussing it, discuss whether firing, or firing out, for ‘dismissing’ a person, was a traditional English or new American slang. One of them quotes a line from Edward Gilpin’s Skialethia (1598), without comment on its extra obscene meaning because that is not to his purpose; but the New Variorum editor deduces that Shakespeare gave the phrase the same extra meaning. Gilpin is a remarkably ham-handed satirist, and the first five lines of his 39th Epigram all struggle to warn the reader what is coming: the reader is leered at and nudged and cockered up till the clincher comes in the final sixth line:

But I’ll be loath (wench) to be fired out.

The only fun here is that a usually innocent phrase has been given an extra nonce-meaning; and it took a lot of putting in—never was joke-work more of a sweat. If anything, this proves that the extra meaning would seem remote to the first readers. Mr Seymour-Smith tells me that I ‘ignore direct statement’ and that Shakespeare’s line ‘undoubtedly does mean’ a venereal disease; as who should say ‘Why don’t you know the language; that’s the gerundive.’ But people do not have to draf a sick joke into ordinary language, when they are talking straightforwardly, even if the joke is known; and this epigram was almost certainly written later than the sonnet. I agree that it is hard to be sure how much Shakespeare meant; the Lady will keep her affair with the Friend secret till she dismisses him, and then give Shakespeare all the gossip—easy enough, but the phrase does seem meant to be rude to her; calling her a fox-hole or a cannon or something. Still, you can’t have proof.

‘The expense of spirit in a waste of shame’ (sonnet 129) was almost certainly written about the Dark Lady; for one thing, the previous two and the next three sonnets concern only her. Mr Seymour-Smith must assume it is about the Friend, because he asks me whether it too is about ‘social climbing.’ This is his usual trick; Shakespeare did feel himself horribly in the toils of the Dark Lady, and often present his relations with the Friend as innocent by comparison; but Mr Seymour-Smith labours to ascribe all this groaning to the relations with the Friend.

Plays were often written about kings, or dukes ruling city states, because plays are largely about decisions, and the decisions of rulers are felt as momentous by many people; even in their private affairs, they are or were free from ordinary policing to a dramatic extent. Anyhow, Shakespeare expected to continue writing plays about such people, and he must (when about 30) have wanted to observe how they actually behaved. It has nothing to do with ‘social climbing,’ because he went on churning out plays and acting in them, obviously not wasting his time on patrons, as soon as he got his essential start from one patron. But Mr Seymour-Smtih (I am sure) cannot bear to let Shakespeare behave like that; it would be snobbery, the most shameful thing in all the world. He scored off his friend for taking over his mistress by not letting on the mistress had clap, did he? Come now, that’s more like a man, soldierly you might say.

I know that no word of mine will shake this moral preference in the minds of the Christie School, but it strikes me as very odd even for the second Elizabethan age, and wildly unhistorical when applied to the first.

+