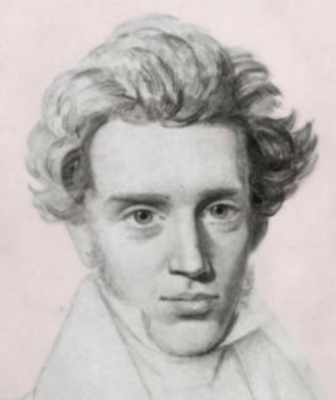

Here, Søren Kierkegaard writes to close friend Emil Boesen about his former lover Regine Olsen, several months after he’d broken off his engagement with her. Kierkegaard was extremely private about his reasons for ending the relationship. Nonetheless, he confided in Boesen, who, as Kierkegaard writes below, was “the only person who ha[d] a seat and a vote in the council of [his] many and various thoughts.”

My dear Emil,

Happy New Year! Thank you for the old one. Thank you for your letter, which in a manner of speaking belongs to both, since I received it in the old and reply in the new.

However, please permit me to make a general remark concerning your handwriting. You write so illegibly that it is terrible. Each letter flows so indistinctly into the next that everything flows together, but such a confluence is not the total impression one might wish.

You ask whether my Elvira is just as interesting close up. In a way I am somewhat closer to being able to answer that question, for this evening I sat in a box unusually close to the stage. You may be dissatisfied with this answer, but I can say no more. Besides, one ought not to make light of such matters, for it is well known that passion has its own special dialectic.

Incidentally, with respect to that affair in which I play the leading role in a manner of speaking (I refer to the one on Copenhagen), it was not terminated in this way, as you surely realize. I have certainly acted responsibly, or perhaps more correctly, chivalrously, and only to that extent perhaps irresponsibly. Surely you understand that I did not intend to make her unhappy. I have never told a single person how the whole business really fits together nor what my intention was. I shall certainly not readily forget that you have been decent enough not to pry, decent enough to remain steadfast, to believe even though you could not understand. In spite of all the attacks by the world, which have left me unaffected, or have merely brought a smile to my lips or sarcasm, you have always been far closer to my true self, for you admonished me constantly to be more considerate of myself. From this it was clear to me that although you could not really figure the whole thing out, certainly you would never accuse me of [exaggerated] egoism but rather of exaggerated sympathy. Not even to you have I wanted to express myself, because I did not consider the matter as settled in any way, and my chivalry forbids me to speak to a third party about my true relationship with a girl. I see from one of your previous letters that she has apparently confided in her sisters. That is her affair. This can neither tempt me to become annoyed with her nor to follow her example, not to the former because in a certain sense I might want it this way, nor to the latter because I am always myself. Through me she has gained a power over me that she never would have gained on her own; I have confided in her the means most likely to bind me, and I have permitted her to employ those means against me. Certainly I need not have done all this, and yet in no way do I regret it. It is and always will be a difficult matter to understand my motives, for I have, perhaps unfortunately, such mastery over my feelings when I want to conceal them that my motives are not easily discovered. It was never my intention to leave her standing between 11 and 5 o’ clock for the rest of her life. If she can hate me, so be it, then she is saved, speaking in human terms. She does not know and never will be told that she may thank me for this. If she cannot, if she still has a glimmering of hope, so be it, then we shall wait and see. I intend to find out about it personally when I have the chance. As I said in a previous letter: to deceive the whole world is a matter of indifference to me, but honestly I do not pride myself on deceiving a young girl. To allow her to sense my enormously tempestuous life and its pains and then to say to her, “Because of this I leave you,” that would have been to crush her. It would have been contemptible to introduce her to my griefs and then not be willing to help her bear the impact of them. She is proud; so is her family in the highest degree. To awaken that in her, to throw her into the arms of her family, to arrange everything so that she came to interpret it as desperate, was the only possible thing to do. To do it is not so easy, and I dare say that my practiced dissembling, my familiarity with passion, etc. are required for it. –This is as much as I shall tell you. I cannot and I will not go into detail here. You have been faithful to me when you really knew nothing and you will surely be no less so now that you see that I, insofar as I think I dare, am opening myself to you. Of course my letters to all other people seem to come from a very different quarter, which is to say that they do not mention her and are always written with a cheerful exuberance, with all possible irony. Whatever I want to hide, I hide, and not even absence and all sorts of mixed feelings produced by absence, etc., can manage to pry me open. I confide only in you. I am used to doing that and I depend on your silence. For heaven’s sake do not say a word to anybody about what I have written here; at the same time I also want to ask you to forgive me for not having told you or written you about it earlier. Once when I was talking with you I dropped a few veiled hints, which you certainly noticed but did not heed sufficiently. I must act as best I can. I confide in no one but you, because I know you can be silent. Suppose some outsider knew my feelings, then all would be presumably be lost. Then I would not find out whether she is capable of hating me. I am not now nor have I ever been the issue. That is what you really reproach me for, but let that be. I am accustomed to mastering my feelings, and they must be silent. I am working, and so, period. I will only say this, that I shall never do anything for her out of pity; she is too good to be treated with pity. Silence! I do understand if you are not really surprised by what I am writing you. If you have anything to say, please write, for you are and always will remain the only person who has a seat and a vote in the council of my many and various thoughts. Write vigorously—and legibly—and quickly—

You ask what I am working on. Answer: it would take too long to tell you now. Only this much: it is the further development of Either Or.

Be strong, my dear Emil! Far be it from me to present myself as a model; but please believe me, I have many sorrows, many difficult moments, but I have not yet despaired. However, the time will come when I must drop the mask before the world as well, must reveal what dwells within me. Surely this will not be a period without trial and tribulation. With God’s help I am not afraid of it. But it was also necessary that I stand alone so that the person in question would first get another impression of me.

Once more, be strong! You have asked me to sustain you. That I cannot do, nor is it perhaps necessary, but still my letters cannot weaken you.

Remember me to your father and mother. My greetings to you, my dear Emil.

Your S.K.

My address is 57 Jägerstrasse, second floor. It would take too long and be too boring to tell you of all the plagues I have suffered with my fraudulent landlord. Now I am living in a good place, spaciously and elegantly, the French doors open to my sitting room, and, God be praised, as always, open to my mind as well.

From Letters and Documents. Kierkegaard, Søren, and Henrik Rosenmeier. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978.