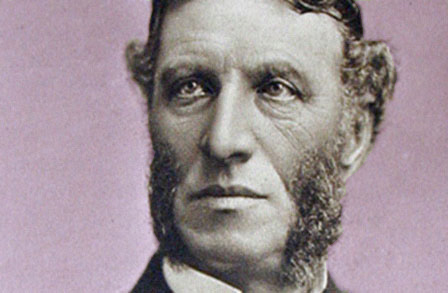

Poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold was deeply involved with contemporary social issues, widely respected as “a man of the world entirely free from worldliness”(G.W.E. Russell in Portraits of the Seventies). In this letter, Arnold writes to Richard Cobden, a liberal thinking and fellow member of the London scholarly gentleman’s club, The Athenæum, about his concern with the destructive nature of English aristocracy and the shortcomings of the middle class to act against it.

To Richard Cobden

The Right Honble Richard Cobden M.P.

The Athenæum

February 1, 1864

My dear Sir

I am much obliged to you for your letter and its inclosure. I most entirely agree with you that the condition of our lower class is the weak point of our civilisation, and should be the first object of our interest; but one must look, as Burke says, for a power or purchase to help one in dealing with such great matters, and I can find this nowhere but in an improved middle class. I believe, with Tocqueville, that the multitude is most miserable in countries where there is a great aristocracy, and I believe that in modern societies a great aristocracy is a retarding and stupefying element; but our aristocracy will not modify itself and English society along with itself; our lower class will not modify them, and one can hardly wish it should, as things are, for it would be a jacquerie: our middle class, as things are, has in my opinion neither the wisdom nor the power to modify them. I know our Liberal politicians think higher than I do of our middle class as it at present exists; I have seen a good deal of it, from my connexion with dissenting schools, and I am convinced that till its mind is a great deal more open, and its spirit a great deal freer and higher, it will never prevail against the aristocratic class, which has certain very considerable merits and forces of its own; and it will not, perhaps, deserve to prevail against it. At the same time, there is undoubtedly just now a ferment in the spirit of the middle class which I see nowhere else, and which seems to me the greatest power and purchase we have; and all that can be done to open their mind and to strengthen them by a better culture should I think be done; we shall then have a real force to employ against the aristocratic force—and a moving force against an inert and unprogressive force, a force of ideas against the less spiritual force of established power, antiquity, prestige, social refinement.

This is how I think my father would have looked at it had he been alive; Mr Disraeli, whom I met last week in Buckinghamshire, said to me of you that you “were born with the mind of a Statesman”; so you will not be impatient with me if I travel a little beyond the bounds of immediate party politics.

Your inclosure I shall venture to keep, unless I hear from you that you want it returned; it is most forcibly and temperately written. I have seen much of France, and have always said that I would infinitely rather, myself, be one of the peasants I have seen and talked to in the most backward parts of France, Bercy or Brittany, than one of the peasants I have seen and talked to in Buckinghamshire or Wiltshire. As for the law of succession of the French Code, that, or something like it, is, I am convinced, a mere question of time; it will inevitably make the tour of Europe. In the old feudal European countries so slight a measure as Mr Bright, following the example of America, proposes, would I am certain prove quite inoperative. But we shall see.

Forgive my troubling you at all this length, and believe me, my dear Sir, with the most cordial respect,

sincerely your’s

Matthew Arnold.—